For the past year or two I have been experiencing a stress that has manifested itself physically. I feel a nearly continuous tension in my stomach, as if I were in a mode of fight or flight, ready for an attack. It’s quite unpleasant to live with this, but I’ve lately found that a daily practice of mindfulness reduces its grip on me. Mindfulness is simply a practice of noticing what one is experiencing in the present moment, without judgement. I begin each morning noticing how my body is feeling, places of tension or relaxation. And if I notice some discomfort or a negative feeling manifesting itself, I look closer, I mentally get a sense of its shape and contours, its intensity. This brings the discomfort from a sub-conscious place into the realm of conscious awareness. Whenever we do this, we give the thing that is bothering us less power over us. In his Rules for the Discernment of Spirits, Ignatius says that the evil spirit wants us to keep things in the darkness. But when we bring them into the light, they loosen their grasp.

Visitors

Visitors

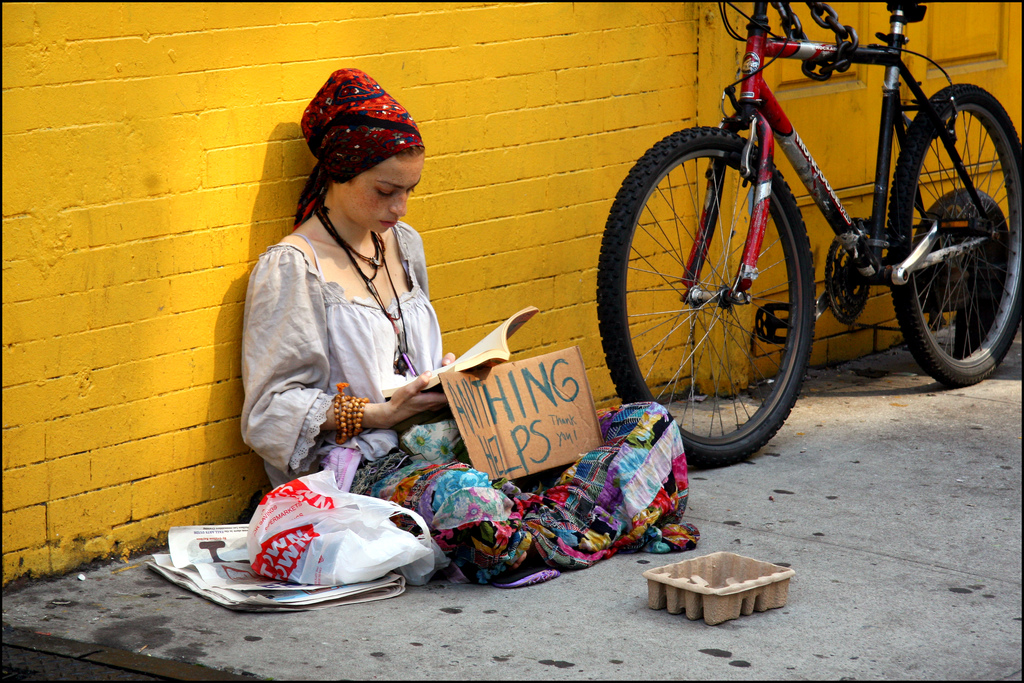

Too often we allow our negative feelings, our pain, and our “enemies” to have great power over us when we push them away reactively. And because it is reactive, it usually happens without much thought: it is unconscious. By examining these things, shining a light on them, we let them be present in the conscious realm. We see them as temporary visitors. The poet Rumi captures this in his poem, “The Guest House”:

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor.Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.The dark thought, the shame, the malice,

meet them at the door laughing,

and invite them in.Be grateful for whoever comes,

because each has been sent

as a guide from beyond.

Non-resistance

There is something to be said for non-resistance. Yet we can see how even something like non-violent resistance is so hard for people to do. To be non-violent is to really be non-resistant to the attack or the “enemy”. If we look at Jesus’ non-resistance, we see that rather than label enemies or law-breakers or sinners, he welcomed them; he befriended them. This was so odd and paradoxical that he was violently killed for it. Yet up to his last moments, he practiced non-resistance. His true resistance came in not giving in to the power of violence and evil.

This is what it means to have a contemplative stance. If contemplation means “a long, loving look at the real,” then we don’t exclude anything from that gaze. We see the real of both joy and sorrow, comfort and pain. In the Spiritual Exercises we ask for the grace to share in both the sorrow of Christ’s passion and the joy of his resurrection.

When we compartmentalise feelings as good and bad, we are unconsciously welcoming some of these guests and excluding others. Jesus’ eating with sinners is a beautiful symbol of the way he first welcomed. He never excluded. He asked a question to someone and listened to their response. What do you want me to do for you? Do you want to get well? What are you afraid of? Why did you doubt? His questions are invitations to contemplation, to pausing and looking at all the things we are experiencing.

The Weeds and the Wheat

The Weeds and the Wheat

Ignatius understood everything as ways God could communicate. In other words, nothing is dismissed as a messenger. So we must examine our feelings for the wisdom they contain, how they move our hearts, what they teach us, and where they draw us.

The parable of the wheat and the weeds teaches us to allow all things to grow together rather than immediately resisting the weeds. Christian language like “spiritual warfare” or preoccupation with damnation can be a disservice to contemplative seeing and the kind of non-violent resistance Jesus practised. We’re quick to fight back and violently resist negative feelings, “sinful” thoughts, or anything we deem “of the evil spirit.” This is understandable when we’re taught to pursue good and avoid evil, but this reactiveness does little to actually move us toward Christian growth or to a place of compassion and deep love. In fact, it makes us quicker to judge and to shun and to marginalise those whom we place in the category of “bad”.

Being a contemplative—being like Jesus—means to first welcome and befriend. This means we bring the person or feeling or thought into the light of our consciousness so we can see it and can examine it. We can discover where it is coming from and how we might respond to it. Do we allow it to stay or can we say goodbye? This mindful approach to our spiritual and emotional life reduces the grip things have on us. Rather than an emotion or feeling or our ego controlling us, we place it before our consciousness and we get to decide what kind of power it has over us. Sometimes we can’t usher it out, and so we let it live beside us for a while until it’s time to leave, but we don’t allow it to overwhelm us.

Ignatius said that the evil spirit is like a child or bully – give in and give them what they want and they’ll only demand more. Parents know that children will often push their parents’ buttons just to see their reactiveness at work. They feel a power in that. Similarly, when we immediately resist something we deem “negative” we amplify its power, whether it’s guilt, shame, anger, frustration, or any kind of suffering. Contemplation and mindfulness redeems and reframes these things, allowing us to live in a greater place of freedom.

What “enemies” do you find yourself resisting? How can they be welcomed and reframed in some way?

> There are some great apps that can guide you in mindfulness practices. I use the Calm app.

Listen to our newest meditation, “Uninvited Guests”:

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

I think I’ll be more contemplative now. Listen more. Speak less. Love more and hate less. Thank you for the article.

I started an MBSR class yesterday and found this post today. What a wonderfully spiritual, clear explanation of a mysterious (at least to me) process. Very grateful for this perspective.