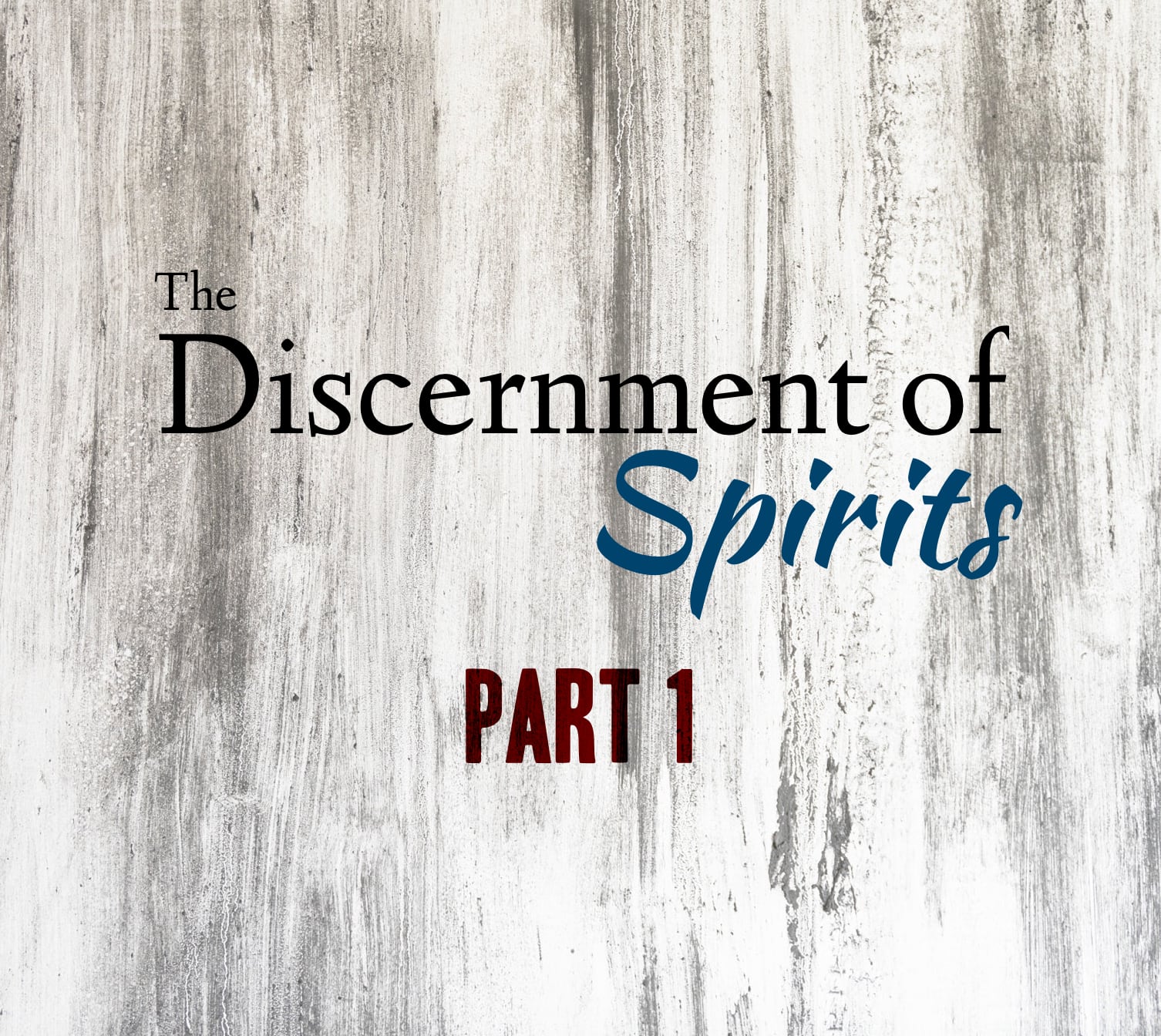

The other day I stumbled upon something called “The Fear and Greed Index” on CNN.com. Its figurative needle swings from one end to the other, indicating which emotion is driving the market. Fear or greed? CNN notes that “many investors are emotional and reactionary”. This index can help investors determine whether stocks are fairly priced. “The theory is based on the logic that excessive fear tends to drive down share prices, and too much greed tends to have the opposite effect.”

Screenshot from www.cnn.com/markets/fear-and-greed

What a sign of the times. To state that fear and greed are the only two motivators for investment! Is it too naive to hope that a desire for the common good can influence the market? Is altruism unrealistic? John 3 says “The light came into the world, but people preferred darkness to light” (v. 19).

Fear and greed are classic characteristics of desolation. Desolation provokes anxiety and can move us into self-absorption and hopelessness. Ignatius clearly states that making decisions in desolation is a terrible idea. A key principle of good discernment is asking ourselves what is driving our decisions. There are at least a dozen accounts in the gospels where Jesus is pushing back on the human tendency to store up riches or put money above God and neighbour. Let’s look at a two examples:

The Parable of the Rich Fool (Luke 12:13-21)

When someone in the crowd asks Jesus to tell his brother to divide his inheritance with him Jesus responds, “Take care! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of possessions.” He then tells the story of a man who had an abundance of crops, and out of greed decides to raze his barns and build larger ones to store his grain. The man figures he can relax, eat, drink, and be merry. But then God calls him a fool, saying that he will die tonight and that these “riches” will be worth nothing. The rich man in the story is driven by greed to hoard his possessions.

The Rich Young Man (Matthew 19:16-30)

We all know this one, where a wealthy man asks Jesus how to have eternal life. Jesus tells him to sell his things to the poor and follow him. The passage says the man “went away grieving, for he had many possessions.” The young man is driven by fear of losing his wealth, which prevents him from embracing Jesus’ call to generosity and sacrifice.

Generated by Midjourney

Fear is a powerful driver. “What if” and “should have” questions can cause us to cling more tightly to the things we have and have “earned”. Margaret Silf says that real freedom is the ability to choose “without fear of loss, and without hope of gain.”

Catholic social teaching offers a compelling vision of an economy driven by solidarity, not self-interest. The principle of the universal destination of goods reminds us that God intends the earth’s resources to be shared equitably among all people. As St. John Paul II put it, “God gave the earth to the whole human race for the sustenance of all its members, without excluding or favouring anyone.” This challenges the notion that our financial decisions should be motivated solely by personal gain. Similarly, the preferential option for the poor calls us to prioritize the needs of the most vulnerable in our economic choices. Rather than acting out of fear of scarcity, we are invited to trust in God’s abundance and to use our resources to serve others, especially those on the margins. Catholic social teaching thus provides a solid foundation for reimagining our economy in light of the Gospel.

Desires

So what can we do to counteract the very human drivers of fear and greed? Ignatian spirituality invites us to truly examine our deep desires, not the surface-level ones for riches, honour, and pride, but our God-given longings – for meaning, beauty, justice, relationship. When we are in touch with that we are propelled not by scarcity and self-interest but by a sense of abundance and concern for others’ flourishing along with our own. Deep holy desires are outward-facing, generative, rooted in love.

Consider the poor widow who “invests” all she has in the temple treasury (Mark 12:41-44). In this act Jesus witnesses, there is no greed. There is no fear. One imagines the widow making this offering in a radical act of trust, from a place of deep desire for God. For her, abundance and riches are likely more heart-deep than wallet-deep.

What might it look like to have an “Altruism and Abundance Index” alongside the “Fear and Greed Index”? To lift up examples of economic behaviour driven by nobler aspirations? Can we have an economic model that considers the person and promotes the common good? It starts with desires that are rooted in love, not self-interest and ego.

Ignatian spirituality invites us to get in touch with those deeper desires and to trust that they come from God. It’s a gradual process of learning to choose consolation over desolation, love over fear, generosity over greed. And it happens through many small, daily choices – including how we spend our money, how we invest, how we show up in the workplace and the marketplace.

No one is immune to fear and greed; they are part of the human condition. But we can grow in recognising their influence and choosing a different path: An economics of communion, not competition. Abundance, not scarcity. Altruism, not egoism.

Related posts:

- The Motivations Beneath Desires: Why They’re Important

- Narratives of the Soul: Unearthing Our Desires through Story

Listen to the podcast version of this post…