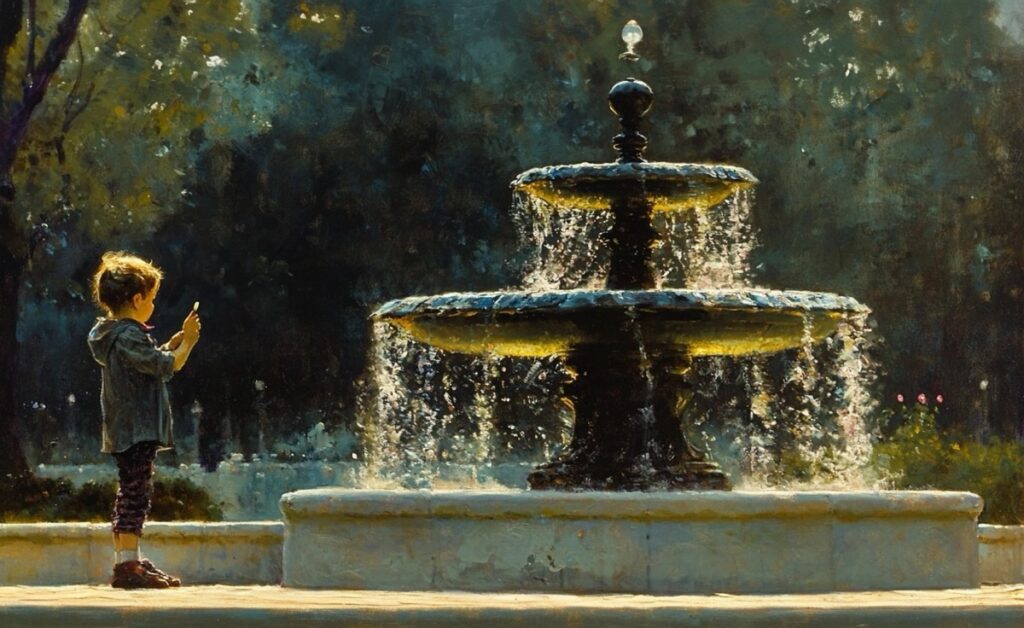

The other day I was at the Atlanta Botanical Garden with my children, and my daughter asked if she could toss a coin into the fountain at the entrance. She took two coins out of her purse and gave one to her younger brother. “You have to make a wish,” she told him. Once they each threw in their coin, she told him, with enthusiasm, that their wishes would come true.

That got me considering how we often view prayer, almost as a magic spell that makes our desires come true. I remember the times when I was a hospital chaplain when families would be praying for a miracle even though their loved ones’ declining condition was beyond all hope. Even today, when people speak about prayer in this way, I find myself uncomfortable. I think it’s because I see prayer as more about my relationship with God than having a sense of control over the world.

It’s All Smoke

I appreciate the honesty in the Book of Ecclesiastes. The author sees the absurdity and randomness of life. He talks about how he has worked hard and enjoyed pleasures of all kinds, but at the end of the day, it is all smoke – it is all passing. He sees the good suffering and the evil triumphing. And throws his hands up saying, What’s the point of it all? We all die in the end. We take nothing with us.

“Humans and animals come to the same end—humans die, animals die. We all breathe the same air. So there’s really no advantage in being human. None. Everything’s smoke. We all end up in the same place—we all came from dust, we all end up as dust. Nobody knows for sure that the human spirit rises to heaven or that the animal spirit sinks into the earth. So I made up my mind that there’s nothing better for us men and women than to have a good time in whatever we do—that’s our lot. Who knows if there’s anything else to life?” (Ecc. 3:19-22, The Message)

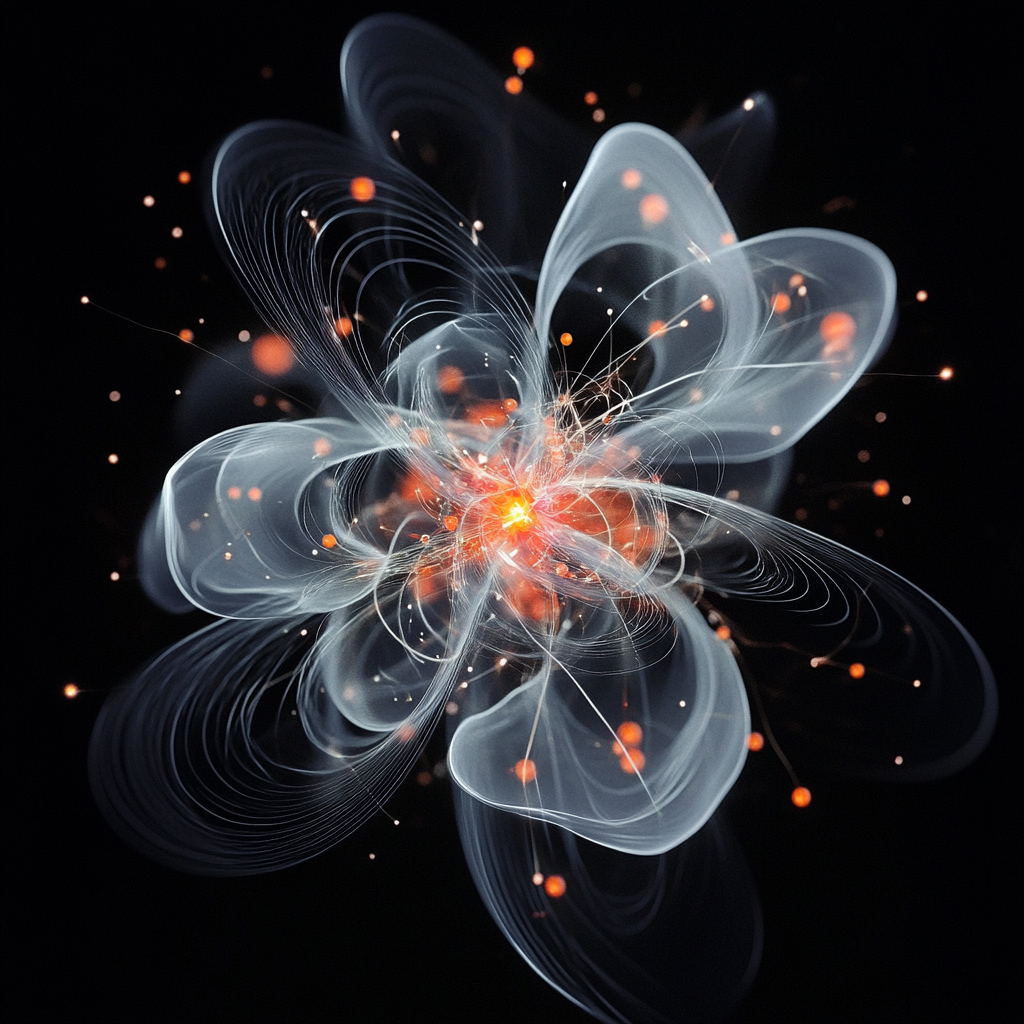

We’re all dust, aren’t we? I’ve lately been struck by the reality that all of the atoms that make up the world and me and everything I love is mostly empty space – electrons orbiting nuclei. Empty space, yet seemingly solid, seemingly real. Empty space, yet I have subjective experiences and emotions and feelings. What are they? Synapses between neurons, chemical reactions. And what is consciousness? Science struggles even to make sense of this – is it an emergent property rising up mysteriously through the complexities of our human body?

Is it all smoke and mirrors?

When my kids threw the coin in the fountain, I realized that we have a natural human impulse for meaning-making and a sense of control. When our prayers are seemingly answered, we attribute the outcome to our prayer. When my house is spared in a hurricane, I attribute that to God’s providence, despite the destruction and loss of life elsewhere.

Meaning-Making

Meaning-Making

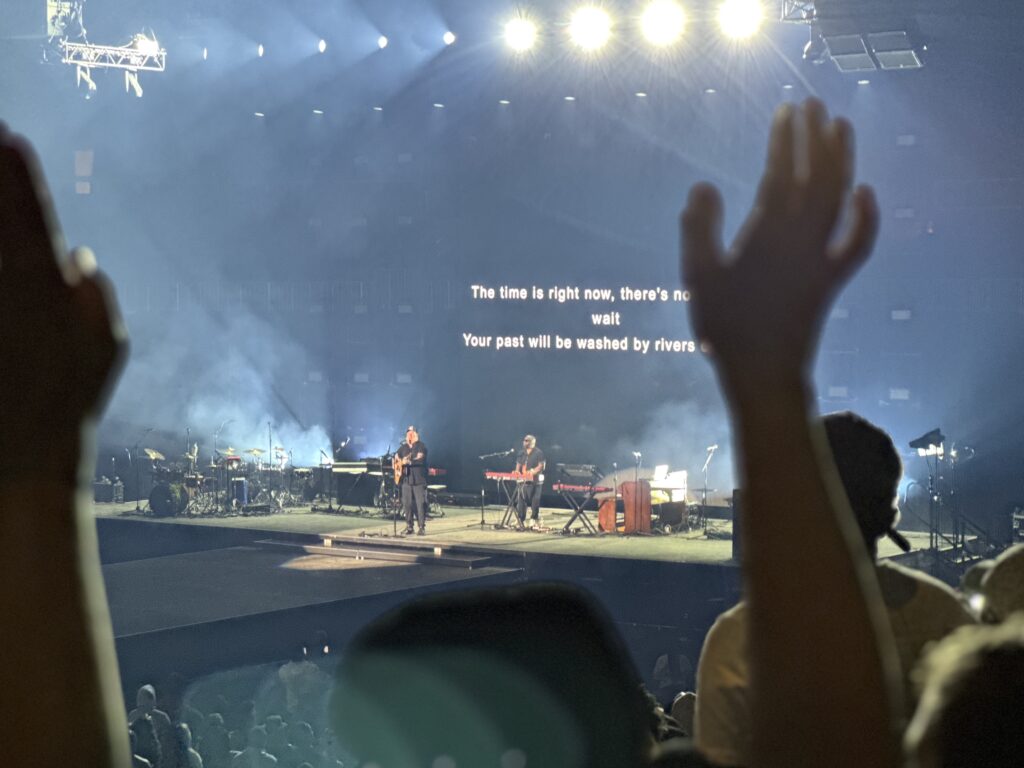

I recently attended a praise and worship concert. As I sat in this packed stadium, I looked around at the faces of the people around me and saw how God was a source of meaning and purpose for them. All these people in one place finding hope and purpose in God. But is this blind human meaning-making? Is this all smoke, as the author of Ecclesiastes puts it?

Next to me at the concert was a Gen Z girl who was engaged in the depth of her own worship experience. Yet every so often she’d pull out her phone, rapidly switching between apps: liking and responding to text messages and social media posts, scrolling and swiping. It was so fast it only seemed to take a few seconds, and I wondered how much sincerity there was in her quick responses and post likes. I realize that even in this space of deep engagement with meaning in God, we still struggle with superficiality and authenticity – especially in a digital age.

I recently read the book God, Human, Animal, Machine by Meghan O’Gieblyn, a former fundamentalist Christian who writes about the intersection of technology, consciousness, religion, and meaning. She asserts that as technology and artificial intelligence progress, humans have lost a sense of control or meaning that religion initially offered. So, humanity is shifting toward using technology to restore our sense of immortality. Theologians like Ilia Delio see this as a continuation of God’s creative process. O’Gieblyn, on the other hand, attributes this to our spiritual longings but also our need to be above all other creatures. “So deep is our self-regard that we projected our image onto the blank vault of heaven and called it divine,” she writes.

As we navigate between meaning and mystery, we can fall into the trap of oversimplifying our spiritual lives, assuming my prayer magically controls reality or changes God’s mind, assuming “everything happens for a reason”. When I am spared from suffering, do I attribute it to God blessing me but not others who are not spared from suffering? Am I falling prey to the Texas Sharpshooter fallacy, which says that we tend to focus on the “hits” while ignoring the “misses”? This cognitive bias occurs when we cherry-pick data to find patterns that support our beliefs, much like a sharpshooter who fires at a barn wall and then draws a target around the bullet holes. In a spiritual context, this fallacy can lead us to overlook the complexity of life and attribute divine intervention to random events, potentially distorting our understanding of God’s role in our lives and the world around us.

Embracing Mystery

Embracing Mystery

In the book of Job, Job finds God in mystery rather than explanation. When Ignatian spirituality seeks God in all things, it doesn’t dismiss suffering. Rather, it embraces it as mystery and discovers that God’s goodness and grace can somehow emerge from the darkest moments.

Can we move from causation to connection, rather than attributing specific events to God’s hand? The key question becomes: Does the meaning we find in an event draw us closer in relationship with God? This perspective allows us to see God even in randomness and coincidences, embracing the mystery that emerges from life’s unpredictability.

This speaks to a good theology of prayer, being more about my relationship with God than about control. David Fleming, SJ says, “Perhaps expressing what I truly want from God may [act] as a preparation of my inner being for an openness to God’s entrance into a particular area of my life.”

At the end, the author of Ecclesiastes finds meaning in God. “All is gift,” so we might as well enjoy it. He accepts the seeming mystery and absurdity of it all, trusting in the mystery of God. Perhaps my daughter’s fountain wish—which was probably a wish for a dog—helps her be more aware of her love for animals. Perhaps praying for a medical miracle for our loved one can be less about changing the biological and physical processes of the universe to bend in our favour, and more a recognition of our hope for new life.

The author of Ecclesiastes gives me comfort. For that writing to be a part of the Bible tells me that I can question and doubt and wonder about the mystery of it all, trusting that somehow, someway, God is in it all.

Related Posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

Meaning-Making

Meaning-Making Embracing Mystery

Embracing Mystery