The other day I came across a conversation on Facebook about giving food or money to someone begging on the street. It surprised me how many people said they would never give money, as most people use it to buy alcohol or drugs. It seemed like big assumption to say that “most” would use the money for destructive purposes. One commenter suggested most beggars were faking. Look at the person’s shoes, they said, to determine whether the person asking for the money was legit. If they had nice shoes, it must mean they’re not really poor.

The other day I came across a conversation on Facebook about giving food or money to someone begging on the street. It surprised me how many people said they would never give money, as most people use it to buy alcohol or drugs. It seemed like big assumption to say that “most” would use the money for destructive purposes. One commenter suggested most beggars were faking. Look at the person’s shoes, they said, to determine whether the person asking for the money was legit. If they had nice shoes, it must mean they’re not really poor.

This whole conversation got me thinking about gift-giving. There can be a lot of baggage and expectations around gifts, but God the Gift-Giver offers us a beautiful understanding of gift-giving.

Ignatian Wisdom

St. Ignatius begins the Spiritual Exercises with this:

All the things in this world are… created because of God’s love and they become a context of gifts, presented to us so that we can know God more easily and make a return of love more readily.1

In other words, all is gift. And these gifts come from God’s love. Love gives way to a gift given. The recipient may then be moved to respond in some way. But how they respond is their choice. This is our first important point: a gift respects the freedom of the recipient. As God allows human beings the freedom to make choices or to accept God’s love or reject it, a gift-giver must have the freedom to let the recipient decide how to use the gift or respond to it.

Anthony de Mello says the same about love. It is gratuitous and free. Those are our second and third points: An act of love expects nothing in return, and there is nothing coercive about it.

What is gift-giving but an act of love? Have you ever received a gift with strings attached? You’re expected to return the favour somehow or use the gift in a certain way, lest you offend the giver. A gift given with generosity should not involve guilt! I cannot tell you how many people I’ve met who are afraid to get rid of something they no longer have use for because it was a gift. And the gift-giver would be disappointed if they disposed of it. So they bring it out each time the gift-giver comes over just to show they’re using it. When a gift is given, the giver ought to be free of it, not still clinging to it.

What is gift-giving but an act of love? Have you ever received a gift with strings attached? You’re expected to return the favour somehow or use the gift in a certain way, lest you offend the giver. A gift given with generosity should not involve guilt! I cannot tell you how many people I’ve met who are afraid to get rid of something they no longer have use for because it was a gift. And the gift-giver would be disappointed if they disposed of it. So they bring it out each time the gift-giver comes over just to show they’re using it. When a gift is given, the giver ought to be free of it, not still clinging to it.

When de Mello speaks about love being free and non-coercive, he means there is no manipulation. An act of love, like the giving of a gift, ought to leave both the giver and the receiver completely free. Too often gifts become a means to manipulate, whether it’s to “prove” love, create guilt, or get something in return. Or gifts can feel more like an obligation rather than an act of love.

Giving to Strangers

Let me take this wisdom back to the conversation about giving money to a person on the street. I used to be concerned about a beggar using money to buy booze, so I would instead insist on buying them food (only if I had the time). I was blind to the coercive nature of this gift (You can only have it if you use it for food). This came from a stance of mistrust and thinking that I knew better. By insisting I buy them food, I was the one in control. I disrespected their agency to be responsible and their dignity of choice. They asked for money, not food. I was not truly free to give a gift because I didn’t respect the person’s freedom or what they were asking.

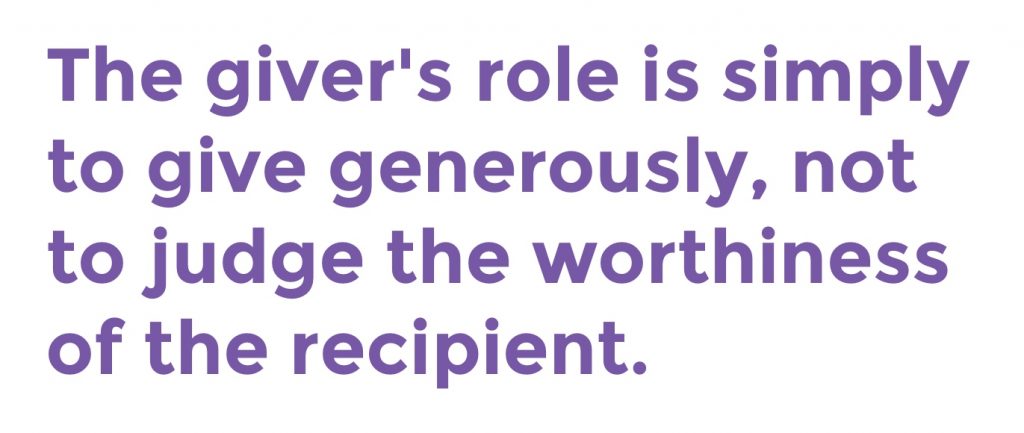

The giver’s role is simply to give generously, not to judge the worthiness of the recipient.

To foster our freedom, my wife and I have a charity category in our budget. If someone approaches us and asks for money, we’re not wondering if we can afford it in the moment. That worry can often lead to justifying judgement of the person asking. Do they need the money “enough” for me to give it up? Do their shoes look ragged enough? Instead, we can feel free to give, with no strings attached. And if we can spend time and converse with the person, then we’ve offered the greatest gift of dignity and human respect.

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

[1] David Fleming, Principle and Foundation from Draw Me Into Your Friendship.

YES! Thank you for this reminder.

Thanks, Andy. I hadn’t thought of giving from this perspective. I used to carry Subway cards to give the homeless because I wanted to “feed the hungry.” This is more generous, more open-handed.

Poverty/homelessness issues are super complex. Removing judgment, the FB conversation you reference was no doubt filled with people just trying to do the right thing. May I suggest that advising that giving—to any person asking for money—is always the best/better way can be just as morally burdensome and run contrary to AMDG. (Discernment Wk 2:Rule 4 – Enemy appears as angel of light). Yes, everyone should be treated with dignity and gifts ought to be given without control motivations. Putting that into action in complex situations requires discernment. In that context, expensive shoes might just be the tail of the serpent?

Hi Andy, You tweeted out with a link to Richard Rohr’s homily and how it “really enriches my last post on gifts.”. I agree and I would also refer to one of my heroes, the late John F. Kavanaugh S.J. and his book “Following Christ in a consumer society”. I read his book back in 1981 and the revised version in 1991. Thanks for your insight!

I used to be hesitant to give to someone begging in the streets. But someone made a good point to me that changed my thinking. What they use the money for says something about them. Whether I give them money says something about me.

For years, I made gift bags for people on the streets holding up various signs requesting help of some sort. Having worked with this population, I knew some things that they may be able to use – soap, toothpaste/toothbrush, gloves, hat, socks, and a $5 gift card for McDonald’s. They could choose what to do with the items in the bag – use them, sell them, or give them away. In warmer months, the bag also contained deodorant and wipes.