Forgiveness can be one of the most misunderstood concepts we have to grapple with. Our religious traditions can sometimes teach that we have to earn forgiveness from God or another, or that even an apology is required. God’s forgiveness doesn’t seem to be given freely. It’s treated less as a gift and more as something that must be bought. Many in the Catholic tradition may treat the Sacrament of Reconciliation not as a chance to hear the healing truth of God’s forgiveness but as a test of our repentance. Are we contrite enough? Will the priest forgive me? Somehow we have forgotten about the cross’ assurance of forgiveness.

Let me first speak about forgiveness between two people.

Freeing You and Me

Freeing You and Me

Forgiveness is a gift of love and of trust. As Jesus calls us to love our enemies, we are called to forgive those who have hurt us. Forgiveness is not a condoning of another’s sin or actions, but a releasing of our own resentment and anger toward them. I love the explanation given by Mister Rogers, played by Tom Hanks, in the movie A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood. He said that forgiveness is “releasing a person from the feelings of anger that we have toward them.” It lifts a weight from our hearts. Is this selfish? Is the only motivation to forgive another so that we can be relieved of a burden? No, God is the one lifting the burden from us. Through our action, God transforms and softens our heart. The anger and resentment is released.

There is a power in self-transformation. Not being able to forgive can be the source of festering anger, and anger keeps us in our ego. This is exactly where the evil spirit wants us to stay. Harbouring resentment keeps us within ourselves. Forgiveness moves beyond ourselves into a trust of God’s love and into the possibility of redemption for the person who harmed us. In a guest post on forgiveness, Mel Davis wrote, “Without that crucial forgiveness, the anger becomes corrosive and degenerates into hatred.”

Jesus knew the danger of anger. In his Sermon on the Mount he equates anger with killing. Healthy anger regarding injustices we see can motivate us to good change, but unhealthy anger can spiral into hate and even murder. Jesus’ bold reinterpretation of the Law aligned with his mission of drawing people toward God and one another (the Greatest Commandment). He went so far as to say that reconciliation with neighbour was more important than a sacrifice to God. “Leave your gift there before the altar and go” he said. “First be reconciled to your brother or sister, and then come and offer your gift.” (Matt. 5:21-26) He knew how easily we can harbour resentment and anger and can spiral into hate and division.

The opposite of forgiveness is resentment, retribution, and revenge.

But what about the other person, the person who harmed us? Must I accept them back into my life and risk being hurt again? Not always. Forgiveness does not mean forgetting the true damage of the hurt. While Jesus sought for people to reconcile and be in relationship, he knew that conversion had to be mutual. When we offer the gift of forgiveness to another, the other person may not accept the gift. This is a consequence of a love that is given freely, expecting nothing in return. Forgiveness may spark a transformation in our own heart but it may not in the other person. It would be dangerous to accept an untransformed abusive person back into our lives.

Forgiveness is a means to your freedom and my freedom. It frees my heart from anger and resentment, and offers that freedom to the other, whether or not they accept it. Forgiveness accepts the truth that the one who harmed me is still a beloved child of God. I entrust that person to God’s care and let go of my own need to change them. This is a true act of love and letting go.

Forgiveness is a means to your freedom and my freedom. It frees my heart from anger and resentment, and offers that freedom to the other, whether or not they accept it. Forgiveness accepts the truth that the one who harmed me is still a beloved child of God. I entrust that person to God’s care and let go of my own need to change them. This is a true act of love and letting go.

God’s Forgiveness

God doesn’t hold resentment toward us, so forgiveness does not lift a burden off of God as it does for us. So why does God forgive? Because again, forgiveness is a means to freedom. And Ignatius would say that God is always desiring us to remove any blocks from our lives that inhibit our freedom to love and live fully. Louis Savary says, “God willingly forgives our sins so that we can get back to the important work of transforming the world by our loving service of each other.” Mercy is God’s default. Like Teflon, sin doesn’t “stick” to God.

Mel Davis points out in her post that without forgiveness there can be no love. In his encounter with the sinful woman in Luke 7, Jesus said, “Her sins, which were many, have been forgiven; hence she has shown great love. But the one to whom little is forgiven, loves little.” Love and forgiveness are entangled. Since without forgiveness there can be no love, God’s forgiveness is part and parcel of God’s love. God forgives before we even realise we need forgiving. It is the way God loves. But sometimes we need to hear the words of forgiveness; we need to claim its reality. Look at all those who approach Jesus. Jesus doesn’t so much do the forgiving but names the reality of the forgiveness. It is the person’s faith or love that proves their forgiveness. This is why Jesus states that the woman’s sins have been forgiven, “hence she has shown great love.” She seemed to have already been forgiven before she performs these acts of love for Jesus.

The Endless Flow of God’s Mercy

The Endless Flow of God’s Mercy

God’s forgiving us is not because somehow our actions have stopped the flow of God’s love, or that God has stopped being present to us. Ignatius envisions God’s love like an endlessly flowing fountain. We may shield the flow in some way, but the flow does not stop. The word in the Bible for repentance, metanoia, means a change of one’s mind, even a “turning around” back to God. God’s love is not dependent on some conditional forgiveness, God’s love is constant forgiveness. When we accept this reality, we “turn around” and stop shielding the flow of God’s love and mercy.

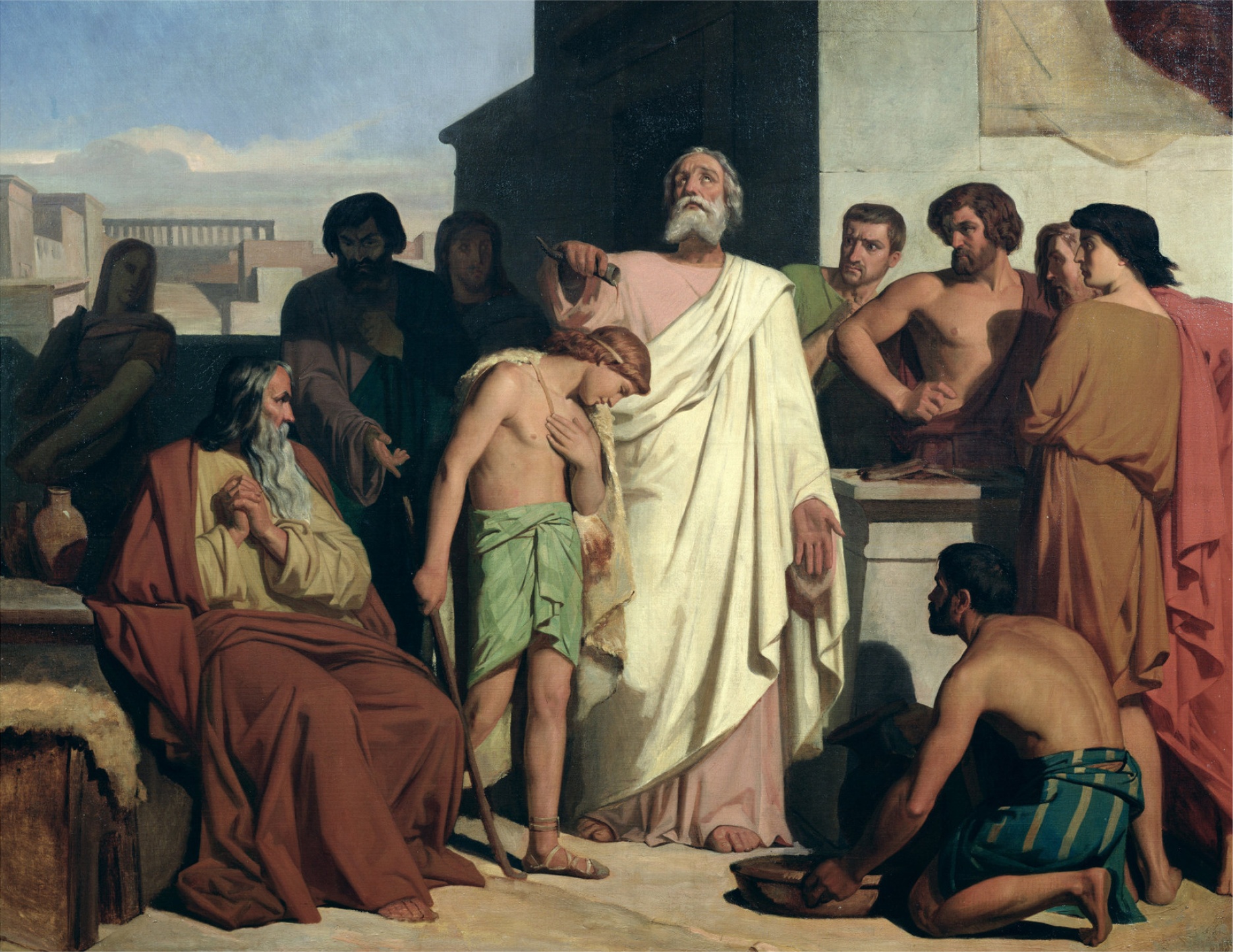

In the story of the Prodigal Son, the son literally turns around and returns to his father. Before the son could even get his words of confession out, his father embraces him. Repentance is not confession, but turning around and un-shielding the love already present. The prodigal son’s words are not what move the father to celebrate him, rather it is his turning around, his metanoia.

We become part of this ever-present flow of love and mercy whose wave we carry through our forgiving others, drawing us, one by one, into the freedom God desires for us.

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

“I Will Arise”

Words by John L. Bell © 2002, WGRG, c/o Iona Community, Scotland, GIA Publications, Inc., agent

Music by Tony Alonso and Recording © 2008, GIA Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. Reproduced by permission of the publisher.

Really nice article on forgiveness. I’m in the process of doing a teaching on forgiveness. You have included the major points I have found, and have added some additional details and new “twists” especially with the scriptural examples. Thanks.

Good article🙂 I’m actually preparing a word for our homecel group topic on forgiveness thank u