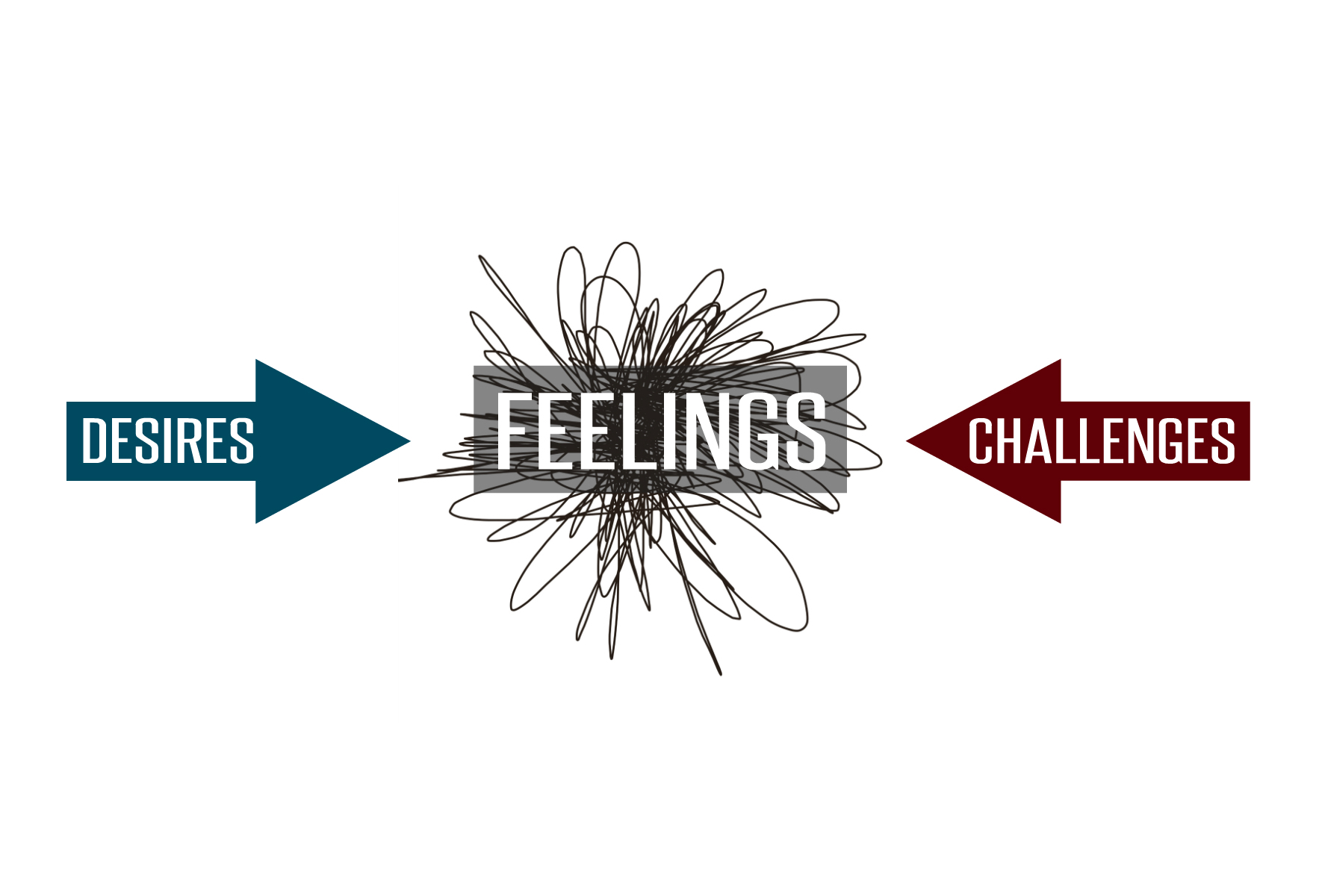

If the most recent US presidential election tells us anything, it shows us that human beings are complex. Yet we tend to assume people are simple and can be boxed into this group or that voting bloc. We appear polarised because our group or tribe or party makes us think we need to take up their more extreme position.

Franciscan Richard Rohr believes that institutions tend to treat people as simple, whether that be a political party, a government, or a religion. Rohr states:

“As a general rule, I would say that institutional religion tends to think of people as very simple, and therefore the law must be very complex to protect them in every situation. Jesus does the opposite: He treats people as very complex—different in religion, lifestyle, virtue, temperament, and success—and keeps the law very simple in order to bring them to God.”

I think the institutional complexity we see in the church comes from a place of care. Rule after rule, guideline after guideline, was added over time to address new situations that arose in people’s lives. But what happens is that these rules become a means of social control, replacing the tradition of spiritual discernment.

If-Then-Else Rules

If-Then-Else Rules

As someone who accompanies engaged couples through the wedding process as well as people preparing to become Catholic, I find I have in the back of my mind a whole slew of if-then-else rules about baptism and marriage. What kind of baptism was it? Was there a previous marriage? Was it a civil or a Christian wedding? Was one spouse Catholic? Were they baptised? Which denomination?

And sometimes even the so-called church experts on these things need to consult the official church law. We find the same complexities in liturgical rules about who can handle the sacred vessels, what material they’re made of, who can and cannot preach, posture, vestments, etc.

Again, such rules developed over time as a way to safeguard a sacrament or vocation or solemn ritual, but they can become overprotective, like a parent who hovers over their child’s every move, preventing them from learning through experience. In other words, when we treat people as simple, we need to create elaborate rules to “protect” them.

Rather than the “law” creating unity, it creates uniformity. Rohr says, “The ego is much more comfortable with uniformity, people around me who look and talk like me, and don’t threaten my boundaries.” The law creates division and tribes.

Trusting People

Yet Jesus understands that no law can perfectly meet people in their human reality. Consider how Jesus distilled 613 complex Jewish laws into two simple commandments: love God and love your neighbour. Rather than dismissing the law, he revealed its essence. This radical simplification wasn’t about making things easier, but about focusing on what truly matters – relationship with God and others. His wisdom lay in knowing that when people grasp these core principles, they can navigate complex situations with discernment. He sees people as complex creatures and meets them where they are. He takes the risk of allowing people the freedom to be themselves and to love God according to the shape of their own heart, soul, body, and mind. We never hear Jesus say “Go and follow these detailed rules so you don’t screw up.” Instead, he offers some core values and invites people to go and live their lives.

Complex rules often represent an attempt to control and standardise rather than trust in people’s capacity for authentic spiritual growth and discernment. The irony Rohr points to is that by trying to protect people through complex rules, institutions can actually limit the very complexity and uniqueness that Jesus embraced.

Consider Jesus’ encounters with those on the margins. With the Samaritan woman at the well, he engaged her complex reality – her ethnicity, relationships, and spiritual seeking – not with judgment but with understanding that led to transformation. When faced with the woman caught in adultery, rather than enforcing the letter of the law, he challenged her accusers’ simplified view of justice and honoured her dignity as a complex human being. Both women found new life not through rules but through being truly seen and trusted. In other words, Jesus trusts the individual to discern their way forward. Catholic tradition holds the conscience to be paramount in discerning the spirit of God moving us toward wholeness. Sadly, institutions don’t always trust that people have the capacity to make good choices.

Structure Yet Freedom

In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius included ‘Rules for Thinking with the Church’ which, in their original 16th-century context, emphasised blind obedience to church authority. While these rules may seem to reflect the institutional control mindset of his time, modern interpretations acknowledge the importance of informed conscience and thoughtful engagement. Today, we understand these rules more as guidelines for maintaining unity while respecting diversity, balancing respect for tradition with openness to the Spirit’s ongoing work. (For a contemporary interpretation that emphasises freedom and discernment, see here).

In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius included ‘Rules for Thinking with the Church’ which, in their original 16th-century context, emphasised blind obedience to church authority. While these rules may seem to reflect the institutional control mindset of his time, modern interpretations acknowledge the importance of informed conscience and thoughtful engagement. Today, we understand these rules more as guidelines for maintaining unity while respecting diversity, balancing respect for tradition with openness to the Spirit’s ongoing work. (For a contemporary interpretation that emphasises freedom and discernment, see here).

I’ve recently taken improv classes and appreciate some of the wisdom that improv can bring to this discussion. Improv teachers will give you some rules and structure, but at the end of the day, there aren’t rules – the core principles serve as guidelines rather than restrictions. There’s a paradox there, isn’t there? The rules create structure and safety for beginners but then it enables creativity and freedom.

Ignatian spirituality provides a healthy approach to freedom and discernment. Ignatius uses a phrase, that in Latin is “tantum quantum”, which says that we ought to use created things “insofar as” they help us grow closer to God. This is not the same as saying there are no restrictions or that all law is bad. Rather, it allows space for our human complexity, that black and white rules don’t always serve our complexity well. This approach echoes Jesus’ way of honouring the deeper purpose of law while recognising human complexity.

Rules ought to serve our relationship with God and one another rather than replace it. We must trust in people’s capacity for their growth and discernment.

I think Richard Rohr wants us to remember Jesus trusted people. He saw their potential even when they didn’t see it in themselves. And that’s what we’re called to do as well.

When we treat people as complex beings capable of growth and discernment, we follow Jesus’ example of trust. Rather than building more elaborate rules to control behaviour, we’re called to create spaces where people can authentically encounter God’s love and guidance. This requires courage – the courage to trust, to allow for messiness, and to believe that God works through our human complexity rather than despite it.

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

I appreciate your use of Fr. Rohr’s work. I subscribe to his daily meditations and also to your blog. In this one, I do wonder how you reconcile the rules when you counsel couples. An inlaw of mine who is Catholic recently married a divorced man because he had been “married on a beach.” I was so upset I had to leave the room for a moment when I heard. Soon I will undoubtedly hear that heterosexual and divorced couples can marry in the Catholic Church if they crossed their fingers during the previous ceremony. Brought up Catholic, I am now a member of the Episcopal Church. I am a lesbian and when I married my spouse 25 years ago in the Metropolitan Community Church, my sister threw me out of the family (She, her husband and three children – the only family I had), seeing this action as a Catholic “cross” she had to bear. I had cared for her children many times in their childhoods. Now one nephew wrote to me that he didn’t want to “expose” my relationship to my spouse to his children. I am very fortunate that one of her children, my other nephew, stuck with me and even attended my wedding. However you choose to write about rules and trust, the Catholic Church hasn’t changed much, except perhaps to get more members.