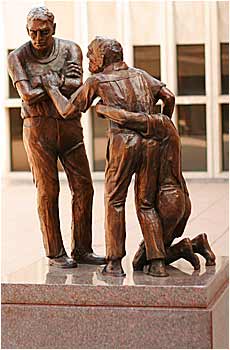

One of my favorite parables is that of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32), which Jesus directs at the Pharisees and the teachers of the Law as they grumble about him welcoming and eating with sinners. Whenever I reflect on this parable, Margaret Adams Parker’s sculpture ‘Reconciliation’ comes to my mind. This is a bronze sculptural representation of the parable, found at the Bovender Terrace of Duke Divinity School. It has a young man on his knees with his arms flung around the waist of a frail and exhausted elderly man. The father’s attention, however, is not on the younger son. Instead, he looks up pleadingly at his older son, who has his face turned away bitterly and his arms crossed. The father has one hand holding up his younger son, and the other grasping the taunt arms of his elder son. The tender gaze of the elderly father haunts me, as they seem to look deeply into the elder son that is lurking within me, not with eyes that admonish but with an insight of vulnerable trust that even the most hardened of hearts can relent.

One of my favorite parables is that of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32), which Jesus directs at the Pharisees and the teachers of the Law as they grumble about him welcoming and eating with sinners. Whenever I reflect on this parable, Margaret Adams Parker’s sculpture ‘Reconciliation’ comes to my mind. This is a bronze sculptural representation of the parable, found at the Bovender Terrace of Duke Divinity School. It has a young man on his knees with his arms flung around the waist of a frail and exhausted elderly man. The father’s attention, however, is not on the younger son. Instead, he looks up pleadingly at his older son, who has his face turned away bitterly and his arms crossed. The father has one hand holding up his younger son, and the other grasping the taunt arms of his elder son. The tender gaze of the elderly father haunts me, as they seem to look deeply into the elder son that is lurking within me, not with eyes that admonish but with an insight of vulnerable trust that even the most hardened of hearts can relent.

Parker’s sculpture raises for me an important point: that reconciliation is God’s initiative and how its obstruction may be caused by us seeing ourselves as dispensers rather than channels of God’s merciful love. Like the older sibling, many of us struggle to make sense of God’s bountiful compassion. Like the older sibling, we fall into the trap of self-righteousness that judges the father’s actions as not only unfair, but also as utterly wasteful. “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends” (Luke 15:29). The result is a hardened heart that is unable to rejoice for in the eyes of the older sibling, his younger brother does not deserve this celebration as he has squandered his share of the inheritance.

Yet, the point of the parable is precisely this: we cannot put a box on God’s mercy that breaks itself free for all through Christ. This does not mean that God condones evil in the world as mercy also obligates us to conversion. The focus of repentance has tended to be on the younger sibling. Then again, in contemplating the father’s gaze in Parker’s sculpture, might we also be invited to repent from not squandering God’s mercy, withholding it as if it were ours to possess in the first place?

In his column “On Not Being Stingy With God’s Mercy”, Fr. Ronald Rolheiser writes, “Mercy needs always to be tempered by truth. But sometimes the motives driving our hesitancy are less noble and our anxiety about handing out cheap grace arises more out of timidity, fear, legalism, and our desire, however unconscious, for power.” He goes on to challenge us, “We need more to risk God’s mercy.” The parable in Luke’s gospel ends with these words from the father to the elder son: “You are always with me, and all that is mine is yours” (15:32).

How’re we hearing these words today? In what ways are we invited to allow God’s unearned gift of mercy to train our hearts to be generous with others, to be giving and forgiving?