This is part of a two-post mini series on the social and theological implications on the body. Listen to an audio version of this post here.

Karl Rahner makes it a point to quote Tertullian, an early church father, who said, “The flesh is the hinge of salvation.”[1] Our Christian tradition speaks positively of flesh. The Genesis story tells of the creation of fleshy human beings who God says are “good”. The Logos takes on flesh in the person of Jesus Christ. And St Paul often uses the Greek word soma for flesh, which alludes to a new creation in Christ. Tertullian was right that salvation—indeed, all creation and its relationship with God—hinges on flesh. So, in all this goodness, why does the body become so inscribed with socio-cultural “norms” and expectations?

Bodily Worthiness

Bodily Worthiness

In my Western context, society creates certain “standards” for the male and female genders. Women are expected to be thin, without the bulkiness of muscle, but with definition, curves, and a distinct “female figure”. For women, being slightly overweight is seen as unhealthy and looked down upon. “Fitness and slimness become associated not only with energy, drive and vitality but worthiness as a person; likewise the body beautiful comes to be taken as a sign of prudence and prescience in health matters.”[2]

Men have their own definition of worthiness. They are expected to have more bulk, muscle, and visible strength, a certain “roughness”. For men, it’s not about being thin. In fact, being “skinny” is not within societal expectations for men. The word skinny denotes implications of being unhealthy. And fat men seem to be forgiven more than fat women. In the past, being overweight was a sign of wealth. It showed you ate well. For men who cared about their image, thinness was not ideal. Here, the body becomes a clear locus of social power. This has persisted in some ways in the general social acceptance of men who are not thin.

A depiction of me, skinny.

Guilt

From my childhood up until now, it has always been difficult for me to gain weight. Family and friends have always made it a point to remind me that I am skinny. “Put on some weight! Eat more!” I was often told. These comments made me feel that I was unhealthy, that I was doing something wrong. Though I ate normal portions and even snacked a lot, I was made to feel that I wasn’t eating enough. My excuse was that I had a high metabolism.

Metabolism refers to the body’s many processes that regulate the conversion of food, fat, and nutrients into energy. Metabolic rate is how quickly the body converts food into energy. My assumption was that my body happened to do this conversion quick enough that the food was never stored as fat. A high metabolism though is not always the reason for not gaining weight easily.[3] Being naturally thin can be the result of genes, habits, food intake, and other reasons. And I ate generally healthy food and portions. So why was I thin? The unanswerable question to why I was “the way I was” caused me feelings of shame. Why was it socially acceptable for someone to call me, a male, skinny, but not to call a woman fat? This always bothered me.

Body-Soul Hierarchy

Double standards like this may originate as far back as the ancient and medieval philosophers who placed soul and body in a hierarchy. They saw the body as corrupted, useless flesh that must be animated by the soul. The soul was the seat of the intellect and while the body was united with the soul, the body was still at the bottom of a dualistic hierarchy. This extended to a male-female hierarchy. St Augustine placed women’s inferiority in the bodily dimension and so did Thomas Aquinas but Aquinas reduced women also in the spiritual realm. “Woman is defective and misbegotten,” he said.[4]

Since women were pegged with the corruptibility of the body there is more focus on the body of the woman than on her intellect. Since men were identified with the soul and intellect, there is generally less concern about their bodies: whether fat or thin, it doesn’t matter. For women, their body is their only concern so image matters more.

Pope John Paul II, though he attempts to uphold women’s equality in Mulieris Dignitatem, maintains a hierarchy. Alluding to the Genesis story, the pope says, “the woman is immediately recognized by the man as ‘flesh of his flesh and bone of his bones.’”[5] He calls out two particular vocations of the woman: virginity and motherhood, two vocations that focus on the woman’s body. Even Mary, who he offers as a model, is emphasised as (and perhaps reduced to) the God-bearer. “The ‘perfect woman’ (cf. Prov 31:10) becomes an irreplaceable support and source of spiritual strength for other people, who perceive the great energies of her spirit.”[6] But, this is predicated by God’s trust in the woman as mother entrusted to birth and care for the human being.

Pope John Paul II, though he attempts to uphold women’s equality in Mulieris Dignitatem, maintains a hierarchy. Alluding to the Genesis story, the pope says, “the woman is immediately recognized by the man as ‘flesh of his flesh and bone of his bones.’”[5] He calls out two particular vocations of the woman: virginity and motherhood, two vocations that focus on the woman’s body. Even Mary, who he offers as a model, is emphasised as (and perhaps reduced to) the God-bearer. “The ‘perfect woman’ (cf. Prov 31:10) becomes an irreplaceable support and source of spiritual strength for other people, who perceive the great energies of her spirit.”[6] But, this is predicated by God’s trust in the woman as mother entrusted to birth and care for the human being.

For man, he is the life source, the one from whom woman came. There is an implication of strength here, of which the opposite could be imaged as fleshless bones. Growing up, I was not only skinny, I was bony. You could see my ribs and my joints were also quite bony. “You’re skin on bones,” my mother used to tell me. As the sense of stigma persisted around my boniness, I was afraid to take off my shirt at the beach. I didn’t want others to see me as unhealthy, lacking in “manly” strength, or “wasting away”. Where did this negative socio-cultural inscription come from? I blame not just charities marketing images of emaciated starving children, but also our religious tradition.

Boniness

Boniness

Christianity has not always been approving of “boniness”. The first image that comes to mind is Jesus crucified who has traditionally been depicted as skinny and emaciated, with ribs visible. Psalm 22, which Christians believe foreshadowed the passion, says, “All my bones can be seen. My enemies look at me and stare.”[7] For me, Jesus’ ribs were always the first part of his body to be noticed. And why would it be any different for me shirtless at the beach? The bony and “ribby” Jesus on the cross evokes an image of not only weakness, but death.

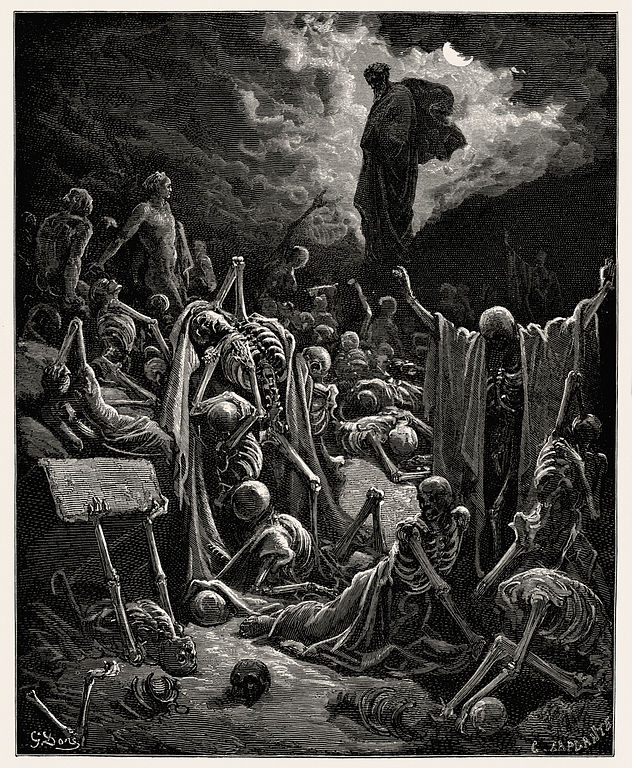

In the Hebrew scriptures, the prophet Ezekiel has a vision of a valley full of dry bones. It’s a lifeless place and the Lord shows a desire to bring these bones back to life. “I will give you sinews and muscles, and cover you with skin. I will put breath into you and bring you back to life.”[8] In this vision, bones symbolise death. They are to be covered up with the symbols of life: flesh and skin.

We have lost our respect for bones because flesh is seen as what is life-giving. Flesh gives our bodies the safety of life. Our bodies use flesh to protect us and can use flesh as sustenance when food is not available. Yet ribs protect our life-sustaining organs, our bones give us structure and support for our flesh. Bones are essential to maintaining our bodies just as flesh is.

Reclaiming Positive Boniness

Reclaiming Positive Boniness

Christianity offers some positive response to bones that are seemingly lacking in life. First is the symbol of Adam’s rib, which we should not see as producing a gender hierarchy but rather a symbol that is life-giving. From Adam’s rib bone comes new flesh and a new human body. The Ezekiel story can also be perceived as hopeful for bones. “God said to me, ‘Mortal man, the people of Israel are like these bones. They say that they are dried up, without any hope and with no future.’”[9] Yet God breathes life into the bones. There’s a hidden life in the bones, unperceived at first. This is the hope that’s hidden in the emaciated-looking Jesus on the cross—the hope that comes three days later, an enfleshed risen Jesus.

While this hopeful imagery offers a positive affirmation of bones it is problematic in that healthy skinniness is seen not as something to be accepted and appreciated as is, but something to be redeemed and hopefully enfleshed. Skinniness remains stigmatised and something to be corrected.

There is another extreme persistent in a society that seeks a “perfect” body. Cheap calories and junk food is now making fatness a social stigma, rather than a sign of wealth. While men have generally been able to “get away” with being overweight, I perceive growing shame around eating because of the prevalence of fast food and cheap calories. Consider the shame created around food by the people who called Jesus and his disciples gluttons and drunkards.[10] Modern science, however, reveals that there are many causes of being overweight.[11] Is there a middle ground that society accepts? It seems that the common perception is that one is either too thin or too fat. The accepted “middle ground” are the bodily expectations that tend to be inscribed on men: lean and muscular, yet not bony and not fat.

Because naturally skinny bodies become a site of socio-cultural inscription, expectation, and stigma, we need to cultivate an appreciation for boniness. I am not speaking of people who are dangerously thin or suffer from eating disorders. I speak of those who are healthy, full of energy and life, but are naturally skinny or bony. The tradition, which has usually been negative about boniness, can offer positive imagery. Bones need not be placed in a hierarchy with flesh. We ought to reappropriate theological and religious inscriptions of bones on the body as essential to maintaining the structure and life of the body, giving protection to the organs and flesh.

Finally, we ought to dismantle the body-soul hierarchies and the different standards imposed upon men and women; this includes skinniness and fatness. Many campaigns exist today that attempt to dismantle the unnatural expectations for female bodies, but there are very few, if any, that foster social acceptance of men who do not fit social bodily inscriptions or expectations. If the flesh—and inclusively, bones—is the hinge of salvation, as Turtullian suggests, why do we place so much social, cultural, and religious burden on it?

Read last week’s post: The Body & The Curse of Looking Young

Listen to an audio version of this post…

[audio http://traffic.libsyn.com/godinallthings/The_Body__Skininess.mp3]Music by Kevin MacLeod

[1] Karl Rahner, Theological Investigations (1981), v. 17, 77.

[2] Mike Featherstone, The Body: Social Process and Cultural Theory (1991), 183.

[3] Mayo Clinic.

[4] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I, q. 92 a. 1.

[5] Mulieris Dignitatem, 6.

[6] Ibid., 30.

[7] Psalm 22:17, GNT.

[8] Ezekiel 37:6ab, GNT.

[9] Ezekiel 37:11, GNT.

[10] Luke 7:34.

[11] See http://www.washingtonsblog.com/2012/04/were-overweight-because-were-not-eating-enough.html.