“Spirituality is always eventually about what you do with your pain,” says Richard Rohr. There are those of us for whom pain is momentary or fleeting. It arrives in heartbreak or a broken bone. With supportive relationships, rest, and medicine those kinds of hurts are eventually healed. And we move on. But for others, pain arrives as an unwelcome guest who never leaves. It clings to your every action, and weighs you down so much that it drags you into a pit of despair. As a hospital chaplain I was witness to the chronic pain of people with whom I could not relate. I was never in such a place, so no words I offered could ever be adequate. Pain can be such a lonely place because those around us cannot truly know our experience of it. Where is God in such endless suffering and physical pain?

“Spirituality is always eventually about what you do with your pain,” says Richard Rohr. There are those of us for whom pain is momentary or fleeting. It arrives in heartbreak or a broken bone. With supportive relationships, rest, and medicine those kinds of hurts are eventually healed. And we move on. But for others, pain arrives as an unwelcome guest who never leaves. It clings to your every action, and weighs you down so much that it drags you into a pit of despair. As a hospital chaplain I was witness to the chronic pain of people with whom I could not relate. I was never in such a place, so no words I offered could ever be adequate. Pain can be such a lonely place because those around us cannot truly know our experience of it. Where is God in such endless suffering and physical pain?

What pain does

Eckhart Tolle speaks about the “Pain Body”, a part of all of us which feeds on the negative energy of suffering. Any kind of suffering is its food. Tolle’s concept refers to negative emotional suffering but I believe it can be applied to physical pain, too. It’s a bit like Ignatius’ understanding of the evil spirit, which seeks to use whatever it can to create suffering—even amplify it—in an effort to draw us away from God. This is what terrible pain does: We cannot think of God or much else but the pain.

What any kind of unjust and unwelcome suffering does is starkly remind us that we are not in control. “Suffering,” says Rohr, “is the most effective way whereby humans learn to trust, allow, and give up control to Another Source.” It forces us to let go, even when it rips away what we imagined to be our very vocation and dreams. Yet for those who still hang on in hope, their spirituality becomes all about making sense of their pain, even transforming it. Rohr says, “If we cannot find a way to make our wounds into sacred wounds, we invariably give up on life and humanity.”

What any kind of unjust and unwelcome suffering does is starkly remind us that we are not in control. “Suffering,” says Rohr, “is the most effective way whereby humans learn to trust, allow, and give up control to Another Source.” It forces us to let go, even when it rips away what we imagined to be our very vocation and dreams. Yet for those who still hang on in hope, their spirituality becomes all about making sense of their pain, even transforming it. Rohr says, “If we cannot find a way to make our wounds into sacred wounds, we invariably give up on life and humanity.”

In a letter to a young Jesuit who took ill in a serious way, Ignatius said that illness can be an opportunity for exercising greater virtue. He even speaks of the illness as a “visitor”.

“I am sure that you have tried to draw the fruit which God our Lord wishes you to draw from such visitations. In His infinite mercy and love He seeks our greater good and perfection no less with bitter medicines than with consolations that are sweet to the taste.”

For Ignatius, the transformation of suffering into our betterment comes not only in sweet consolations but often in “bitter medicines”. Perhaps this can offer some hope, just as Jesus tasted the sponge of bitter wine on the cross. The path to redemption and resurrection is sometimes unpleasant.

An answer?

An answer?

I don’t believe the mystery of suffering will ever have an answer we’ll be satisfied with. Even God’s explanation to Job’s tremendous suffering was essentially, “You can’t understand my ways.” Richard Rohr acknowledges our bafflement: “Humanity has never known what to do with unjust suffering—which is our universal experience on this earth—until Jesus gives his seismic shift of an answer.” Jesus reveals not a clarity on why we experience pain, but rather he reveals a means for its transformation.

On the cross, Jesus shares in our bewilderment, quoting Psalm 22. “My God, my God. Why have you abandoned me?” And he then surrenders himself to the hands of God in trust.

The interesting thing about pain is that it’s deeply personal and unknown to those outside of us. Our pain resides in hiddenness. Even an intimate partner cannot truly know our pain. They can only find compassion in the pain of their unknowing. Henri Nouwen finds blessing in this hiddenness. He says, “In hiddenness we have to go to God with our sorrows and joys and trust that God will give us what we most need.” God is the only one who can share in our pain, suffer with us, and even grieve with us.

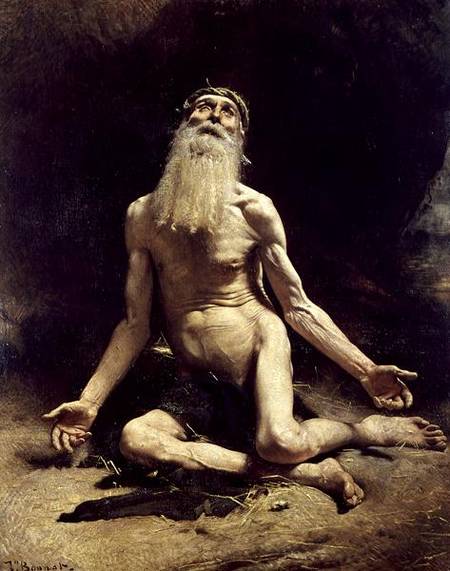

Sometimes our pain means that our relationship with God, for the meantime, is one of crying out in lament. After everything had been taken away from Job and he was covered in painful sores and boils, he laments. “Why won’t God give me what I ask? Why won’t he answer my prayer? If only he would go ahead and kill me! If I knew he would, I would leap for joy, no matter how great my pain.”

Such honesty before God, even in the unfathomable mystery of suffering, shows Job’s commitment to be in relationship with his Creator, even if that relationship feels as if it’s hanging on a thread.

“If my troubles and griefs were weighed on scales, they would weigh more than the sands of the sea.” (Job 6:1-3)

Pain ends

The biblical stories can help us make sense of suffering in faith, but they can also seem unhelpful. The haemorrhaging woman who suffered for a dozen years reached out to Jesus in faith and desperation. And she was healed. Christ’s painful suffering on the cross ended after just a few hours. Even the end of Job’s story was a multi-fold restoration of his life. For those dealing with chronic pain that interrupts their life in the smallest of ways, these stories can be unhelpful. Their pain hasn’t been cured. Their comfort hasn’t been returned.

The word comfort literally means “with strength”—perhaps not physical strength, but rather strength of heart. It’s the kind of strength these biblical characters needed in order to reach out to Jesus, or the strength of honesty of the Psalmist lamenting to God. What these stories do reveal is the deep Christian truth of transformed suffering. Those experiencing great pain can indeed have this kind of comfort: living with the strength to hold on in hope to a relationship with a Christ who transforms pain.

Our hope of the resurrection is not limited to “resurrection moments” here and now, like that experienced by Job or the woman with the haemorrhage. The hope is also for the ultimate Resurrection where suffering is no more and every tear is wiped away. While this moment of new life is not on our own time, we can look longingly toward that moment assured that our suffering somehow, someway, has had some purpose, that the pit of grief has moved us beyond it. Richard Rohr says that “pain teaches a most counterintuitive thing: we must go down before we even know what up is.”

Our hope of the resurrection is not limited to “resurrection moments” here and now, like that experienced by Job or the woman with the haemorrhage. The hope is also for the ultimate Resurrection where suffering is no more and every tear is wiped away. While this moment of new life is not on our own time, we can look longingly toward that moment assured that our suffering somehow, someway, has had some purpose, that the pit of grief has moved us beyond it. Richard Rohr says that “pain teaches a most counterintuitive thing: we must go down before we even know what up is.”

With this mindset we can finally see Pain as a just a temporary guest, doing something in the hiddenness that only God can understand. Along with God we can long for the day Pain bids farewell and the result of her work will be made more clear.

Listen to an audio version of this post…

Andy, thank you for this inspiring and heartfelt post. Suffering is an eternal question in all of our lives. I will use this as the springboard for a discussion with a Bible study that I facilitate.

Dear Andy, I wanted to thank for this article….your timing could not have been more perfect. The paragraph on what pain does supported me during a family visit today. There is a powerful rejection of me by my daughter-in-law and none of us know why. It is like being stabbed in the heart as I try to have the visit….one a year…be as happy as possible for my son and grandchildren. I still have no idea what to “do” but I did manage to say goodbye after 6 hours with them and the kids saying it was the best visit ever. I was peaceful after being ignored for that entire time…sad, feeling sorry for her but not angry. My prayers for help after reading your piece this morning were answered.

Thanks so much, Mary Ann

>

Hi Andy! This is one of your best pieces. Blessings,

Ily Fernandez, CSJ

>

I can’t tell you how much this resonates with me.

Thank you, everyone, for the kind comments. I’m glad this can resonate about physical pain as well as emotional pain. Mary Ann – My church often prays for the reconciliation within family conflicts. I join your family to my own prayers.

Very powerful piece. Thank you for sharing

This resonated with me also! My pain is emotional and sometimes I think I would prefer physical pain! My son and his wife have completely rejected us and their entire family on both sides – not her family. My daughter in law has told my grandchildren that we are the root of their problems and they run from us when they see us – even at church. We are not allowed any contact with them and for years we were very close. I pray for strength to live with this – I have no hope that we will ever reconcile. I pray for my son and grandchildren.

Totally sick of warped Christian pain fetishism. There is NOTHING good about pain and suffering, it diminishes lives and drives people to despair or suicide, maddened by pain. But if fetishism is your thing, fill your boots. Its another matter , however, when you allow others to suffer for your beliefs, such as the erstwhile Bosnian nun who ‘tended’ to the sick in Calcutta. She denied proper pain medication to people because of her beliefs, and all the money that came in never seemed to stretch to comfortable beds for the sick. ( In all the photos I see of this ‘saint’, the sick are always lying on hard floors.)