There’s a pattern we find in scripture that seems to repeat itself over and over again. First, God offers humanity the beautiful gift of life and peace. It’s the original goodness we find in Genesis 1 where God, at each moment of creation, says, “It is good.” In scripture, God’s gift of original goodness is usually pledged as a covenant between God and humans, where peace and goodness is founded upon a firm and faithful relationship with God. But after a while humans fail to live up to their part of the covenant. Their loyalties shift to riches, honour, and pride, the enticements of the evil spirit, according to St. Ignatius. Humanity worships not just a golden calf or another god, but over-relies on human kingdoms (I mentioned this in my post on “The Neighbourhood”).

The Prophet Isaiah writes (24:5):

The earth lies polluted

under its inhabitants;

for they have transgressed laws,

violated the statutes,

broken the everlasting covenant.

Humans break God’s covenant and suffer the natural consequences of this, which appear as God’s judgement, wrath, and war. In other words, we tend to dig our own graves! But the next part of this pattern reveals God seeking to renew the covenant and restore humanity to its original goodness.

Archetypes

Archetypes

The biblical stories that reveal this pattern are like maps that we can use to make sense of and apply to our own life. They are archetypes that reveal a truth – about us, about life, about God. We need stories because we need images that help us make meaning in our lives. Religions are based on stories because these stories give trajectory to the spiritual life. This is why the early Christian communities continued the Jewish practice of reading the scriptures and why we still do today. Stories ground us, keep us connected to our ancestors who experienced similar triumphs and setbacks, and they propel our own stories forward. Consider the stories we tell ourselves, the narratives we grew up with, cultural, religious, familial, national. All of these shape us and give us meaning.

St. Ignatius builds this pattern into his Spiritual Exercises. Someone making the retreat begins reflecting on the goodness of God, the pattern of God’s gift-giving to us, the truth that everything that is exists for our purpose to flourish in a life with God. But then the retreatant spends a period of time reflecting on the sinfulness and brokenness found in their own lives and in the history of humanity. We find ourselves part of a kingdom that is quite incomplete, where human nature means we can be our own worst enemy. And the Jesuit John Veltri points out that the sin and brokenness we pray with does not only include our own personal acts of sin, but the “sin situation” we find around us. We recognize the ways we are a part of sinful systems and narratives, the ways humanity can be blinded to things like racism and seeing the human in the other, our collective ego, and even our own unhealthy habits and tendencies that draw us all apart.

But this is in the context of God’s infinite mercy. We find we are still loved and God is still propelling us toward a final wholeness. The story continues. The Spiritual Exercises concludes with a meditation on God’s endless giving of self to us in an outpouring of love and mercy. It’s amazing. God offers all as gift, and we are invited to respond. And even if our response is to turn away from God, God continues to offer gift! So the Spiritual Exercises relies on the stories of scripture as an archetype of this and our own life with God.

Human Kingdoms

Human Kingdoms

I share all this because I think we can see this pattern playing out in the world today, and most recently in the United States. We have put too much stock and expectation in human government and institution, something the biblical archetype shows will always fail us. When they do, those especially at the extremes of the political spectrum seem surprised. Sadly, they dig in more to the expectation that human institutions will come around to their image of perfection. Politicians are made into saviour figures and government itself becomes the idol we worship. Politics becomes our national religion. And then it fails us again. This cycle, as we’ve seen, leads to violence and loss of many kinds: loss of life, loss of soul, loss of hope. While human institutions and governments are necessary and can do tremendous good, they cannot satisfy all of our longings, dreams, or sense of incompleteness. And they cannot even fully restore the soul of a people who have forgotten their original goodness and to whose kingdom they really belong.

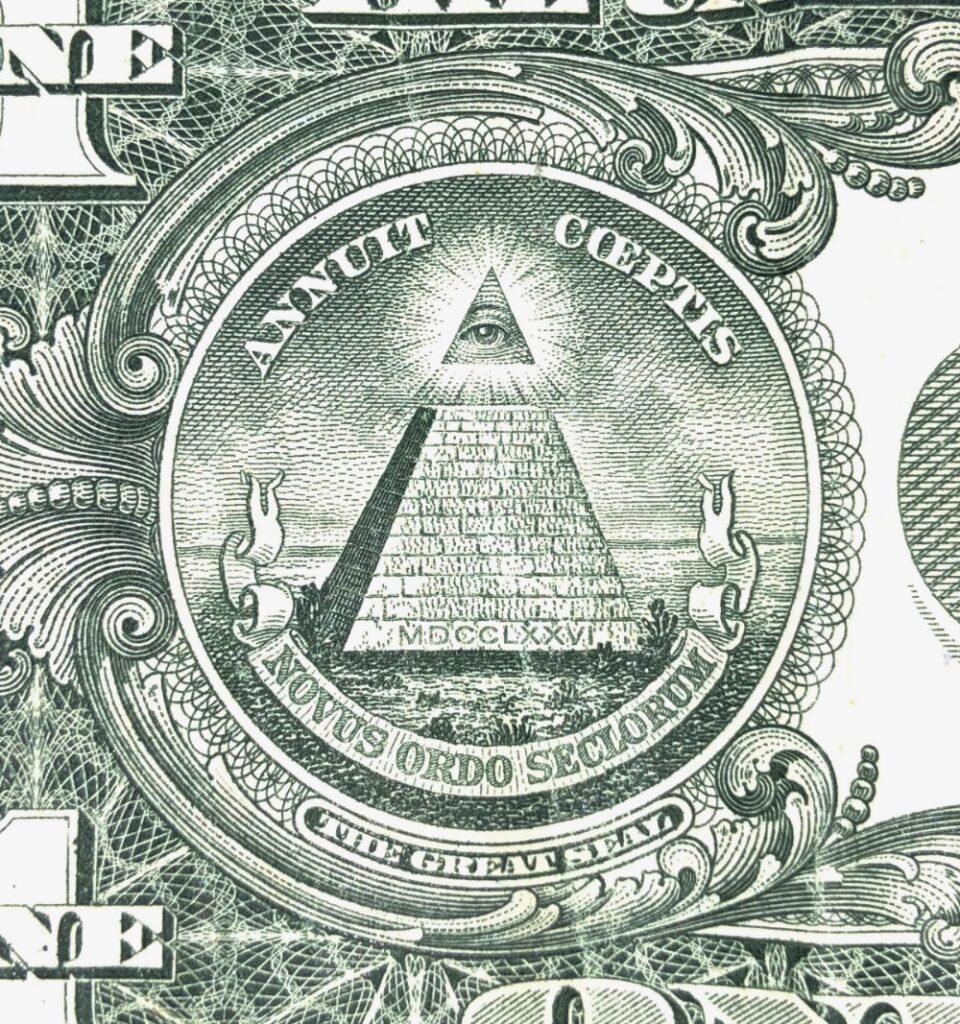

Someone recently drew my attention to this quote from Richard Rohr in his book Adam’s Return. I feel like it captures precisely this political idolatry we’re witnessing:

Someone recently drew my attention to this quote from Richard Rohr in his book Adam’s Return. I feel like it captures precisely this political idolatry we’re witnessing:

How could we not confuse America with the kingdom of God? On our dollar bill, the eternal eye of God is just about to rest on the almost completed pyramid of our empire. Below is written that we are the novus ordo seclorum, “the new order of the world,” and annuit coeptis, “[God] favors what we have begun.” Such an identification of the United States with God’s kingdom, and the pride and arrogance that go with it, remain part of our national consciousness, even if most Americans can’t read Latin.

Yet, despite the waywardness of humanity and the destruction we cause one another and our idolising of human institutions, God continues to promise renewal, gives second chances, and makes new covenants that commit to restoring that original goodness which we keep forgetting about.

A New Order

For Christians the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus becomes the primary archetypal story. Jesus is the ultimate new beginning who gives to us a new way of being human, a new way of understanding God’s faithfulness, and a kingdom that is all about hope. But it’s an “upside down” kingdom: We must die to self in order to find ourselves. We must become blind in order to see. We must carry our cross to find liberation. And even physical death itself gives way to eternal life. It’s a kingdom that finds its power in love, not violence.

Jesus was offering restoration to practically everyone he encountered, whether through a call to follow him into a new life, a physical healing that restored people again to their communities, or forgiveness that restored their own sense of worth and belovedness.

Human institutions are not going to usher in a “new order”. Only God will. What we encounter now in our present world is the “old order”! And God transcends it! We need to orient our human institutions to serving the common good as much as we can, but we have to be careful of making them idols. When we witness the kind of violence we saw on 6 January we have to acknowledge that there was a lot of blindness going on. There was idolising. There was certainly a lack of genuine trust in God. As the prophet Hosea recounts this recurring pattern of humanity, God says “You thought you didn’t need me. You forgot me” (Hosea 13:4-6, MSG). Israel asked God over and over for kings but in the end they failed God. Yet God promises restoration, healing, and love. “I will heal their disloyalty; I will love them freely” (Hosea 14:4). Hosea concludes, “If you want to live well, make sure you understand all of this. If you know what’s good for you, you’ll learn this inside and out.” In other words, can we learn our lessons?

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…