“I could NEVER do THAT!”

That’s often what I find myself saying at times as I delve deeper into learning about Buddhism. This my second semester as the teaching assistant for a comparative religions course on Christianity and Buddhism. It has challenged me personally in ways I certainly did not expect.

If I am truly being honest with myself, my exclamation “I could NEVER do THAT,” in actuality, most often means, “I do not WANT to do THAT.”

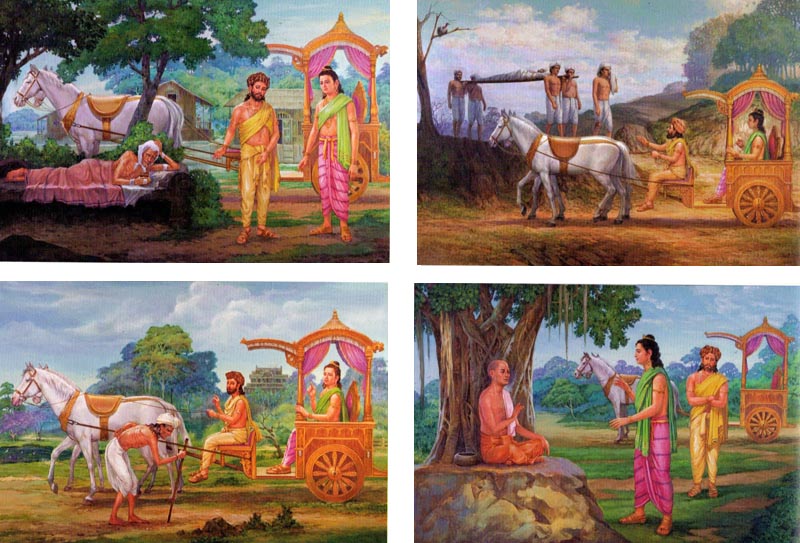

The Buddha’s Four Sights

Desire and Suffering

The Second of the Four Noble Truths tells us that all suffering is caused by desire, or clinging. We cling to certain people, possessions, and achievements. We base our identity on them. In Buddhism, the concept of the self is an illusion. Emptiness, or the idea of “no self,” tells us that we are all interconnected. There is no separate “I” from the rest of the world. We cannot fool ourselves by thinking we actually are our profession, or our gender or ethnicity, or our particular role in a community. At some point, according to Buddhist thought, we have all been one another’s mother or father, son or daughter, brother or sister.

The Third Noble Truth is Nirvana, which represents the cessation of suffering, the state of peace where the process of clinging and self-grasping stops to reveal a clear, infinite, open dimension beyond the conditions of suffering. The path to Nirvana (the Fourth Noble Truth) is often summarized in three kinds of training: ethical discipline, meditative concentration, and penetrating wisdom.

The second point, meditative concentration, is, I think, the hardest for me. This includes a powerful attention to the present moment, an awareness or awakening, which cultivates honesty and seeing clearly. According to Pema Chodron, this does not mean ending the process of thinking altogether, but rather making friends with our thoughts and acknowledging them. This allows us to develop a different attitude toward so-called pleasure and pain.

No-Self

No-Self

“Gain and victory to others, loss and defeat to myself,” Chodron says. This means that we want to share joy with others instead of being stingy about it, as our desire to be “a victorious self” over and against others is at the root of all suffering. Here, we develop a different attitude toward the unwanted stuff in our lives: “we are not just willing to endure it, but to let it awaken our hears and soften us.”

This is scary stuff. I do not want to “accept the present.” I worked so hard in school that it is difficult not to tie my identity to being an academic. I still remember how much anxiety I felt when I was waiting to hear back from doctoral programs. Somehow, I felt that by not sleeping and refusing being in the present moment, I could influence the decisions of the admissions committees. As I am sure my fiancé and my parents will attest, I am quite stubborn! I want to be in control, I want things to go my way! I hate surprises!

Chodron says, “When the world is filled with evil / Transform all mishaps into the path of the Bodhi.” We need to make friends with our feelings of hatred, confusion, fear, etc., so that we can accept them in others. We also need to stop the cycle of blame.

Anger

“The only way to effect real reform is without hatred,” Chodron says. This is scary. Anger is a common emotion I experience. Yet, in the Buddha’s encounter with a woman who was insulting him, he did not send harsh blows her way. He described the woman’s anger with him as a gift: “She offered me a disagreeable gift, and I did not accept it.”

This is hard. I tend to think of myself as a “good person” – I do not make fun of people; I am willing to donate time and money to those in need, yet this really is not enough because I AM FILLED WITH ANGER. When I am kind to others, I often expect them to be kind to me in return. I AM ALSO FILLED WITH BLAME. I still carry a grudge against those who have hurt me in the past (and some who still hurt me in the present), whom I claim have contributed to some of my personal struggles. Somehow, deep down, I feel like anger is the answer – the good old “yeah, I’ll show ’em!”

I want to have compassion for the homeless man on the street, the child who is sick in the hospital, or my personal friends when they are experiencing a crisis. But having compassion for the person who is quite well-off but takes advantage of you; or the person in a position of authority who treats you poorly; or the person who seems to have the resources to care or help but just does not – THAT IS HARD.

And I say I cannot be Buddhist because of what I have written above. It’s too hard, too strange, and too weird. Yet, when I really am honest with myself, that’s a bad reason. Sure, I cannot be ever be Buddhist—namely because I do believe in a personal God, who became incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth. I do not believe in reincarnation and I believe in an eschatological kingdom of God. But, I can and should put into practice this wisdom I have learned from the Buddhist tradition. In fact, I think I must in order to be a better Christian.

So that is my challenge to myself this Lent. To be “slow to anger and rich in love” (Psalm 145:8). It will not happen overnight and it is going to be hard – so I hope all of you will hold me accountable! I do not expect to be a perfect at this by the time Easter rolls around, but I hope to struggle and be challenged, and to perhaps stop letting myself think of “my enemies” as enemies.

Related posts:

Sent from my Verizon Wireless 4G LTE DROID

God

Thank you for an exceptional Lenten meditation. Buddhism is a powerful path for people of all religious faiths.

Many books in my home deal with Buddhism. I have read and reread and agree that the peace of the present moment, the idea of non-attachment are ideas and concepts that appeal to me. However, as you stated, much easier read than done! I have nearly every book written by Thich Nhat Hanh and especially love Living Buddha, Living Christ. I felt he saw what I see. All that being said, I still find the practices hard – present moment, ha! I am usually stressing over tomorrow or feeling bad for what I did yesterday. So I guess I thoroughly agree with you. I am striving for the present moment during Lent. Present moment, beautiful moment! I wish you luck in your Lenten journey!

We have much to learn from others. I also meditate but it is certainly challenging as is living in the present moment. Every day I ask the Lord to help me to be detached, not to cling to things or to other people. I’m doing this at age 70 so I have great hope for you as you are learning this wisdom at a young age. Blessings on your Lenten journey – we will be walking together!

I love this and your honesty, Kate. This piece is definitely challenging me to look at those attributes in myself, and hopefully have a shift in my thoughts and actions.

Thank you!(-:

To be in your position sounds like a truly amazing opportunity. Thanks for sharing what you are gaining.

Sent from my Samsung GALAXY S5