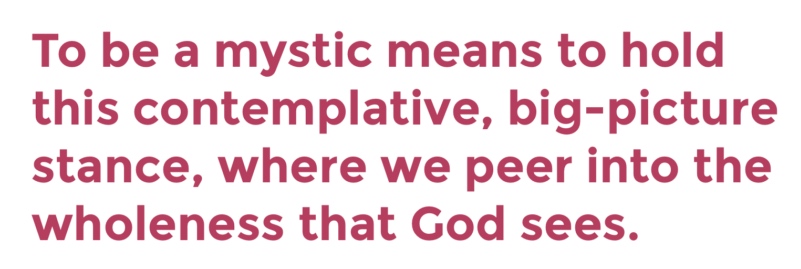

The wisdom of the Examen is that it widens our gaze to see more of the whole—the whole of our lived experience, our context, our world. At least as much as we humanly can see. I like to think of the Examen like looking at the jigsaw puzzle of our lives (or our day), and examining each piece, placing it within the larger picture. This is how the Examen gives meaning to events that can at first seem insignificant. This prayerful reflection can focus us in on a certain puzzle piece, naming it with specificity and nuance. But it also helps us see the context so the puzzle piece makes even more sense.

Now when we’re putting together a section of a puzzle, we don’t need to see the whole picture, but we do need to see the surrounding context for a single puzzle piece to make sense. Without that context, the piece would have little purpose on its own. Only God sees the entire picture. The spiritual life is to see through God’s perspective, to widen our narrow gaze so we can see a bit more of the whole.

Contemplative Stance

To have a contemplative stance means holding as one the many facets of the larger story. We can be a contemplative on the scale of a single day, seeing the parts of the whole during our Examen. And our personal lived experience is its own part in an even larger story of our community, our world, and all creation. Richard Rohr teaches about the “Cosmic Egg“, a metaphor with layers of story: my story, our story, and the story. If we remain in my story and don’t see the larger context, then we’re in danger of remaining in the ego. And if we remain in the tribal “our story” and don’t acknowledge the even larger story beyond that, then our own group becomes individualistic (we see this in religion and politics). When we remain at either of those two levels and think that’s all there is, that that’s “truth”, then we become black and white narrow-minded moralists and excluders. We close up and our Christian identity becomes little more than a flag to wave.

Rohr says, “[Mystics] don’t think one side is totally right and the other side is totally wrong. They can see that each side has a part of the truth. When people on either side of any contentious issue cannot love one another, it means they don’t have the big message yet.”

Rohr says, “[Mystics] don’t think one side is totally right and the other side is totally wrong. They can see that each side has a part of the truth. When people on either side of any contentious issue cannot love one another, it means they don’t have the big message yet.”

There are contentions we sometimes face in our Examen. Do I forgive this friend? Do I trust again? What are the ethical implications of this choice or that?

To be a mystic means to hold this contemplative, big-picture stance, where we peer into the wholeness that God sees, the bigger picture where contradictions can make more sense. We have a jigsaw puzzle of some family photos and there’s always a couple pieces that on their own don’t seem to make sense. The person’s eye seems too close to their mouth. Wait, is that their nose? When I look at the pieces on their own I have a silly Mr Potato Head image in my mind. But when I finally place the pieces into the entire face, I can see how each piece makes sense.

Widening the Narrow View

Widening the Narrow View

Our Christian faith stands on contradictions—in life and in theological questions. Former Jesuit Ruben L. F. Habito who engages with both the Christian and Zen traditions, admits that he lives in the tension of trying to reconcile contradictions. “To be Catholic is to affirm both sides of a theological question. Is it human or divine? Is it three or is it one? Is it grace or is it free will?”

“When somebody has an answer for every question, it is a sign that they are not on the right road,” Pope Francis says. The Catholic tradition has always been both-and.

Many sincere religious people are what Pope Francis calls “new gnostics”, who prize head-knowledge of religion or Jesus than heart-knowledge. It’s about black and white morality, which certainly doesn’t spring from an encounter with the Jesus in gospels who presents a lot of grey through parables and proverbs. The parables, for instance, make little sense if you have a narrow view of God’s love as conditional.

As with the puzzle metaphor, when we focus too closely on a piece, we narrow our view. Spiritual seeing comes when we widen the view, the “frame”, and see the larger picture. When we get caught up in the minutia and details we can truly become lost souls. When we magnify God, for example, and make God so large and almighty like a Santa Claus in the sky, we actually narrow our image of God. God gets truly larger as we mature in our faith. For some, as they hold on more tightly to certitude and answers, God gets smaller and smaller.

Instead of a jigsaw puzzle, imagine navigating a ship. If we’re only looking through binoculars, never looking away, we may see the iceberg but perhaps too late. And we end up reacting to what we see in our narrow view. A good navigator balances her use of binoculars with an expansive view of the whole horizon. This is a contemplative stance, helping the officer intentionally respond to what’s ahead rather than reacting in haste.

Seeing from God’s Perspective

When we use the Examen to see even a portion of our lived experience we are using the dual capacity of our heart: the binoculars and the wider gaze. We recognise the puzzle piece and the pieces around it. But when we pray the Examen we’re also looking at God. We see the intimate activity of God in our day, as well as the larger activity of God in my life and the world. I can even see how no puzzle piece is insignificant.

As Richard Rohr says, “Once I can recognize the divine image where I don’t want to see the divine image, then I have learned how to see. It’s really that simple. And here’s the rub: I’m not the one that is doing the seeing. It’s like there is another pair of eyes inside of me seeing through me, seeing with me, seeing in me. God can see God everywhere, and God in me can see God everywhere.”

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

Widening the Narrow View

Widening the Narrow View

Great read! God bless you. 🙏