If you really read the gospels—I mean really pray with them—over time you’ll discover the simplicity of Jesus’ teaching. Most Christians grow up with some sort of formal religious education, at church or in a religious school. There, much of the focus can be on the complex history of God’s people in the Hebrew scriptures (Old Testament) or on memorising lists of commandments, sacraments, virtues, sins, fruits, gifts, rules, and doctrines. One can come away finding Christianity a convoluted web of precepts and difficult-to-understand stories.

The Essentials Lead to Depth

By Ppvanderlee – Licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0

I have been training to become a catechist for the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, an approach to religious formation using the Montessori approach to learning. In fact, it’s less about “learning” about God and allowing children to discover within themselves their natural desire for God. CGS is active in the Catholic and Episcopal Churches. Using physical materials, figures, dioramas, and various objects, children discover a God of gifts and Jesus, the ultimate gift to us. The story of Jesus is presented and connections are also made to the liturgy. The atrium, as it’s called, is divided into areas that present the essentials of our faith: the mysteries of the kingdom of God told through parables, the mystery of the Incarnation told through the prophets and the infancy narratives, the story of Jesus as the Good Shepherd, the Eucharist, and Baptism. As in Montessori, CGS presents to children just the essentials; no more, no less. Amazingly, a beautiful and simple theology emerges. And rather than beginning children with the allegories of the Old Testament and its often wrathful images of God, CGS begins with Jesus, who is the essential of Christianity. The other stuff can come later.

As I’ve witnessed presentations of biblical stories in the CGS atrium I’m reminded of what St. Ignatius said to spiritual directors in the Spiritual Exercises (annotation 2):

The one who explains to another the method and order of meditating or contemplating should narrate accurately the facts of the contemplation or meditation. Let him adhere to the points, and add only a short or summary explanation. The reason for this is that when one in meditating takes the solid foundation of facts, and goes over it and reflects on it for himself, he may find something that makes them a little clearer or better understood. This may arise either from his own reasoning, or from the grace of God enlightening his mind. Now this produces greater spiritual relish and fruit than if one in giving the Exercises had explained and developed the meaning at great length. For it is not much knowledge that fills and satisfies the soul, but the intimate understanding and relish of the truth.

In other words, he’s asking the director that when they offer someone a scripture passage to meditate on, just to offer the essentials, the facts of the passage and not to impose any meaning or interpretation. This leaves room for the person to have an authentic encounter with God in their prayer. We tend to want to add detail or fluff or over explain or analyse. But we need room to wonder about the mystery of God.

As Ignatius says, “For it is not much knowledge that fills and satisfies the soul, but the intimate understanding and relish of the truth.” A good spiritual guide stays out of the way so that the Creator may deal directly with the creature.

Similarly, in CGS the catechist doesn’t add to or paraphrase the story in scripture. She reads it right from the Bible, and using the materials (like a diorama), makes only the most essential movements and actions of the story. Nothing more, nothing less. This allows the child to fill in the rest with their imagination. It leaves room for them to wonder about the mystery presented and discover the meaning in it for themselves.

Analysis and unpacking theology is great, but we must first relish the mystery of God’s love before we get into the theological nitty-gritty. We must know in the heart and the soul before we know in the head.

Jesus, A Master of the Essentials

As I said, the more you read the gospels the more you discover how Jesus was a master of the essential which led people to encounter the deep wonder and mystery of God. Quite often the scriptures say people were “amazed” or awestruck by Jesus’ preaching. That’s a movement of the soul and a bafflement of the mind.

He boiled down the entire law to just one essential commandment: Love God and love neighbour as yourself.

When the rich young man came to him and asked what he should do to live a life for God he said, sell your things and follow me.

We see in Luke 3, a precursor to Jesus’ teaching in John the Baptist’s encounter with the crowds. It’s not the water of baptism that changes you or your ancestry, it’s living a life that bears fruit, he tells them. When they ask him what they should do he tells them to give their extra coat to someone who needs one, and to give surplus food to one who is hungry. When the tax collectors ask what they should do, he says, “Collect no more than the amount prescribed for you.” And to the soldiers he says, “Do not extort money from anyone… and be satisfied with your wages.”

Could it be that simple? John’s responses seem like simple common sense. Jesus continues this pattern of preaching the essentials: love, be generous, forgive. His lived poverty was a nod to this essentialism. And a spiritual poverty embodies not only a trust in God, but a simplicity of faith; dare we even say faith like a child.

And, like in Catechesis of the Good Shepherd or in the Spiritual Exercises, Jesus offers stories that help people to gain not head-knowledge about God, but to sink into the heart-mystery of God. The parables can be interpreted in many ways, yet there’s a simplicity to them. Often great truths come in the smallest and simplest things, or in the fewest words. The simple realities of a mustard seed, a grain of wheat, water, bread, wine, oil, and light become bottomless metaphorical wells of the realities of God.

Essentials In Your Life

Essentials In Your Life

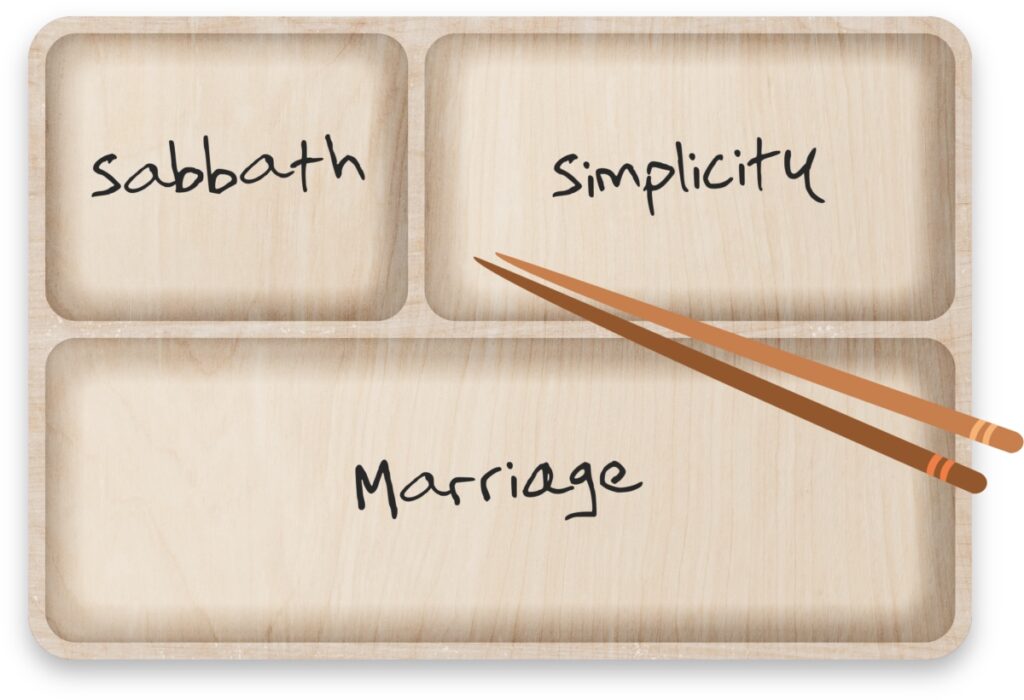

In my last blog post I spoke about essential guiding principles in our lives, those essential values we hold that we organise our life around. I encouraged you to consider three, but perhaps we can name, of those three, the most essential. One helpful tool is a bento box, a simple Japanese lunch box divided into sections of different sizes. Imagine one that has three compartments, one large, one medium, and one small. Which guiding principle or value would you put in each? Which is the most essential in your life? It’s a helpful exercise. I named simplicity, sabbath, and marriage as my three main guiding values. I would likely place marriage in the largest compartment as for me that feeds everything else. Then simplicity would go in the medium-sized section since knowing how to focus on the essentials and to say no to certain things truly gives me sanity. Sabbath would be in the smallest compartment because it’s something that is really a product of my desires for both a healthy marriage and simplicity. It’s interesting that in my example one flows into the next.

How would you organise the important things in your life? What is most essential? What is most life-giving? What leads you most toward loving God and neighbour?

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

Essentials In Your Life

Essentials In Your Life