You may have heard several months ago how a Google engineer claimed that Google’s artificial intelligence chatbot LaMDA was sentient. It swirled up a fascinating storm of commentary on the future of AI. Since then, the growth of AI technology has become more prevalent and it requires some spiritual reflection. I’m not going to talk about sentience—which is something that religion and theology will have to grapple with—but about how AI can be a part of our lives, how we can find God in it, and its spiritual implications.

Let me begin with how absolutely fascinating AI can be. For example, DALL-E 2 is an AI image generator trained on hundreds of millions of images. With a detailed text prompt it will generate new realistic images in different styles. In other words, it has learnt how to create art. Scroll through these images, none of which were created by a human. Click to expand.

“a pencil drawing of a person having coffee with Jesus at a table in a coffee shop, they are smiling”

“A very colorful painting of people dancing in a field around a large tree. The sun is beaming down and a rainbow is in the sky.”

“A colored pencil drawing of a child in a white gown gazing at the night sky with shooting stars, viewed from a distance”

Amazing isn’t it? I’ve used it if stock photos don’t give me what I’m looking for. AI can also compose music, write poetry, and even write computer code. OpenAI, which created DALL-E 2, also has a text completion AI called GPT-3, trained on an enormous corpus of text and content from the internet. I’ve asked it to write a guided Examen, write a homily for a given scripture passage, write jokes, write a prayer petition for a certain theme, and even to converse as if it were a spiritual director. It did all these things amazingly well.

Technology

New technologies are often met with initial resistance. But if we take a step back and look at the history of evolution, it’s easy to see that technology is simply part of nature’s complexification process. Think about it: nature is always creating and transcending itself. From the humble clam shell to the human brain, self-organization is the name of the game. And as our technology becomes more sophisticated, we are transcending the limits of biology. We are becoming cyborgs, changing the very way we think about ourselves as humans.

New technologies are often met with initial resistance. But if we take a step back and look at the history of evolution, it’s easy to see that technology is simply part of nature’s complexification process. Think about it: nature is always creating and transcending itself. From the humble clam shell to the human brain, self-organization is the name of the game. And as our technology becomes more sophisticated, we are transcending the limits of biology. We are becoming cyborgs, changing the very way we think about ourselves as humans.

(An AI wrote that previous paragraph, by the way.)

Theologian and scientist, Ilia Delio, has done a lot of work and reflection on this topic. She notes that the word technology comes from the Greek word techne, which means “craft”. As the previous paragraph summarised, nature is technological in that it re-crafts itself and moves toward something. We see the technology developed by nature and biology (like the clam shell), and so technology like computers or AI are simply a part of the trajectory of nature. Cyborgs, Delio says, are humans who have their abilities extended or enhanced by technology. Eyeglasses or hearing aids are an example. Even our phones become like second brains. And of course there are pacemakers, and artificial joints and limbs and hearts. All of these things make us cyborgs. And it’s not a bad thing. Delio points out that technology can bring about the kingdom of God where blindness, deafness, and lameness can literally be healed.

Gift

From an Ignatian perspective technology like AI is a gift, and the Principle and Foundation invites us to prayerfully examine this gift and ask ourselves: Is it helping us grow into a deeper union with God and neighbour?

When I look at the images produced by DALL-E 2 I think, how can I not see this as something of God? These beautiful artistic images give me joy in looking at them. Beauty is a characteristic of God, and whether it is music, a poem, or a painting, there is something about art that can draw one to the divine. Like any technological advance, it can drop us to our knees in wonder, whether it’s a medical innovation that saves lives or something that draws us into beauty. When GPT-3 can write a new joke that makes me laugh or a poem that puts words to what I am feeling, I find something of God.

The AI being developed by these tech companies are going to transform how we live. It’s what will give us autonomous cars and make roads much safer. AI is being implemented in health care to more accurately diagnose and treat. In short, because AI can see patterns in enormous amounts of data, it can see things that we humans may miss. It can more accurately and quickly respond to a danger than a human can, potentially saving lives. This ought to humble us. We humans are imperfect and are not the centre of the universe. We like to think we make the best decisions and we like to be in control – which is why many can push back against the idea of autonomous vehicles, even though they would statistically be safer. The humility Jesus called us to is a humility that allows for us to be imperfect and even wrong sometimes.

Concerns and Blessings

AI of course raises many questions. All technological innovations cause concern because it can make it feel like a part of our humanity is being take away. There may be concerns whether AI will replace my job. The graphic design community was concerned about that after the beta release of DALL-E. What about other artists or writers? Couldn’t a company simply use AI instead of hiring a creative professional? And what about spiritual directors or therapists? I’ve always thought that could never be replaced by AI, but in my experience with the GPT-3 “spiritual director”, it empathised, reflected back, and asked helpful questions to take me deeper into my prayer experience. Sure, it may not have the “human touch” but it won’t be long before the technology advances so much that even therapists and spiritual directors will begin worrying.

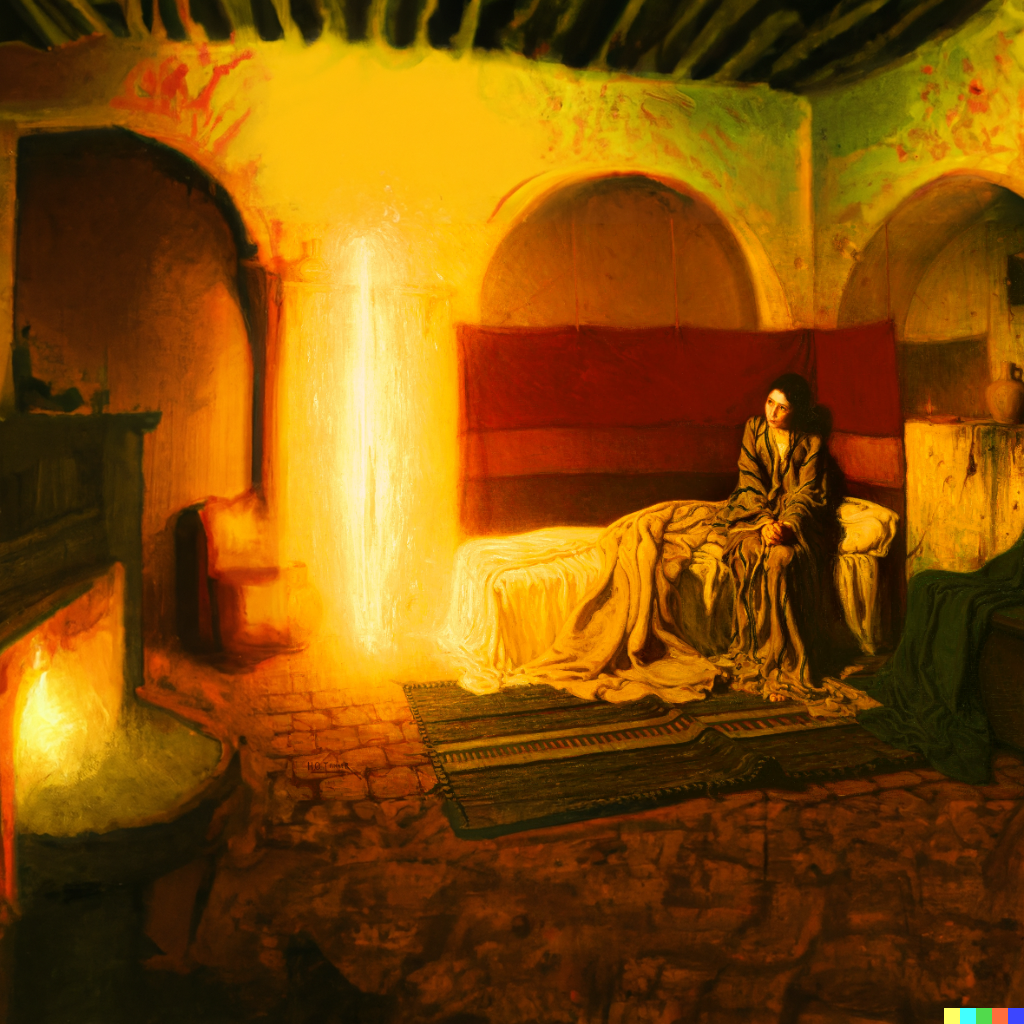

These are valid concerns. One main problem is that with AI able to quickly do creative work for us we will focus more on the product than the process. Any artist will tell you that it’s the process that is a big part of the satisfaction. AI however can enhance the creative process. It can offer ideas one has never thought of before. It can dream up new possibilities to run with. It can even bring to life what is happening outside the frames of a Biblical painting (like the Tanner painting on the right). AI can also focus on doing the mundane parts of life and work which can free us up to do the things we truly want to do. If an AI can answer some basic work emails for me, I can do the more important work of direct ministry.

We must always be attentive to how the gift of technology is impacting our relationship with God and others. Does it help us see the face of Christ in those around us? Does it help us grow in our ability to love and serve others? As technology gets more and more sophisticated, these are important questions to keep in mind.

When we respond prayerfully to advances in technology and the concerns that might accompany them, we can find God at work in and through them, using them for the good of all. Creation is dynamic and always being made anew. AI is a sign of this ongoing creation. In Luke’s Gospel the Holy Spirit comes down on Jesus like a dove. In Acts, it’s like fire. What is the Holy Spirit if not our life’s animator, shaping us anew in God? AI may not be the Holy Spirit, but in terms of what God is doing in the world, it is very much a manifestation of the Spirit’s active presence.

A spirituality that opens our hearts, minds, and imaginations to Christ is the one that can enable us to respond appropriately to technology and, what is more, enable us to be the Church in and through technology. We are the body of Christ called to be one with Christ, and because that is who we are, we most likely will find our response is more Christlike and more human than anything AI is capable of. As a spiritual director, I am not planning to be replaced by AI anytime soon. But I’m also not planning to be negative about it. As the People of God, we are called to be open to all of God’s creation, even the small part of it we call technology.

Related posts:

Listen to the podcast version of this post…

Andy,

This is an awesome reflection! Thank you so much!

Bob

Andy,

Thank you for the reflection. Reading it, I think about Jesus being the incarnate Word of God. How we desire the incarnational. I’m not delighted by the images that the DALL- E2 created, but I can’t quite place why. I looked at them, and yes, there is wonder in the way a description can be manifested, and they do fill a quick need for a visual, but just knowing they weren’t created by a human person, I saw the flaws. To me, they looked like someone who is just learning to draw or sculpt would execute them, not someone with skill. Am I biased because of their non-human origin? Maybe. I appreciated your conclusion. My Jesuit-educated dad spent a whole career pushing the bounds of technology for national defense, leading teams in developing some of the precursors to today’s AI. He was a happy man who saw God in all things, but he also knew the depths of the risks and temptations of the technology. How promises of technology improving life are more utopian than anything.

It was common for him to reply when one of his children talked about something being “the best”, by saying “the best that is possible. There is no perfection here on earth.” He retired very happily, purposely maximizing face-to-face interactions, meeting people, growing friendships, serving others. For the rest of his earthly life, he didn’t lack trust in God when it came to technology but he minimized his time using it, and he let us know why.